Rabbi's Blog

Read morelie = שקר

plank = קרש

Yitro ~ thoughts and actions

Yitro – “Yitro,” is translated as “Jethro”, as in the name of Moshe’s father-in-law. He hears of the great miracles, comes from Midian to the Israelite camp, bringing with him Moses’ wife and two sons. He advises Moses to appoint a hierarchy of magistrates and judges to assist him in the task of governing and administering justice to the people. And then the revelation at Har Sinai, or mount Sinai is described. The famous words – we should be a kingdom of priests and a holy nation. Are said by God, we respond by saying “all that God has spoken, we shall do.” As the revelation is occurring, the people are scared and beg Moshe to receive the Torah and convey it to them. This is one of the few moments when the triennial cycle and the annual cycle have no difference whatsoever, as it would make no sense to read the Aseret HaDibrot only once in three years.

==

Kabbalat Shabbat – important converts

Our reading is famous because of how it is utilized by our Christian neighbors, who are constantly implying that the Ten Sayings are really Ten Commandments, as in THE ten commandments, and there are no other commandments in the Torah. The Jewish tradition respectfully disagrees, and we see the ten sayings as part of a continuous revelation that contains 613 mitzvot, or commands.

The Ten Sayings are called Sayings because they are paired up with different tens, particularly the Ten Sayings that are the basis of the story of Creation. If you go back to Genesis 1, you will find that the words “God Said” appear 10 times. Those 10 times are also connected to the prayer Baruch Sheamar that we say in the morning, in which the word “baruch”, blessed, appears 10 times. In the Jewish mind, all those things are connected in an organic reality, the reality of ten fingers and ten sefirot, in which ten is a number that indicates a basic makeup of the universe.

Our portion has an important characteristic – it is named after a person. There are six parshiot named after people, three non-Jews and three Jews. Noach, Balak and Yitro are the non-Jews, Sarah, Pinchas and Korach are the Jewish ones. But Yitro, Moshe’s father in law, is different than Balak and Noach in which in our very portion, he becomes Jewish. Whereas we do not have really a ceremony for Moshe’s wife Tzippora, there seems to be a ceremony with Yitro. First the translation says that Yitro heard all that had happened to Yisrael from Moshe, then that he was jubilant, then that he says “baruch Ad-nai” and “now I know that Ad-nai is greater than all gods”, he offers sacrifices to Ad-nai and then all the dignitaries of Israel come to eat bread with Yitro.

The word “jubilant” is yached, in Hebrew, that is connected in the midrash with Echad, one. And so of course, say the rabbis, Yitro has joined the Jewish people. It is not just about what he heard – the exodus, according to the plain meaning of the text, or the exodus and the aseret hadibrot, the ten sayings, according to Rashi and the midrash. It is not just that he heard, but that he decides to act on what he hears: he unifies his own experience through the lenses of there being one God, guiding and nurturing and energizing all creation and all creatures.

“Now I know” says Yitro – indicating an arrival. When you talk to converts in general, most of them will express to you this feeling of having come home. Of things finally making sense. Of the experience of exile ending, and a new phase, a moment in their lives that all is connected, and I can see what brought me here, at this moment, even through the darkest periods of my life I see a guiding nurturing force behind it all, lovingly tending to my future.

Jews never think that just a few verses of the Torah get to be more important, and that Torah is reducible to ten verses or even ten actions. Even when Hilel says “what is evil to you do not do to your neighbor” he adds: now go and study. The ten sayings are a portal – and stopping at the portal because you believe that the portal is the castle is to loose the vision of the castle, and forget the existence of a Ruler and a force behind all of it – the path, the portal, the castle.

Yitro, and many others in Tanach, such as Rahav, Rut, the daughter of Pharaoh, Tzipporah, all looked at the entrance and entered into the palace, according to the rabbis. Nowadays, there is an interesting influx of people becoming Jewish, not only in America but worldwide. Entire families, entire communities, go through a process – whether Orthodox, Conservative, Reform – and throw their fate and their future with our people. And the moment they became one of us, two incredible things happen: the collective unconscious gets transferred to them, and they are supposed to be seen like a Jew in all things. Indeed, it is forbidden to remind them of their past, according to the rabbis.

It is not by accident that the portion is named after this character, one who had another religion – if you remember he was described way back as a priest of Midian. And then he joins our people. Yitro is really a stand in for all Jews who have become Jewish after birth, who have chosen the Jewish tradition as home.

May we all merit like them, to choose Judaism as our ethical, moral and spiritual home, seeing with new eyes and a new spirit the story of our lives.

Shabbat Shalom

==

Shabbat morning – eyes for wonder

Count how many times the word “voice” shows up in our reading.

One of the questions of careful readers of our text is how does one understand expressions such as “their saw the voices” at the moment of revelation. Moreover, there are six times when the word “voice” appears in our text, one of those are in the plural, so you could count really seven. One of those voices are of the shofar – and if you recall the extra sentences we say on RH, the shofarot are there, and one of them has to do with the revelation at Sinai.

Now the rabbis in Pirkei Avot say that the shofar that was blown in the revelation moment was from that same ram that Avraham sacrificed in place of Itzchak, AND that particular, metaphysical ram was created together with other NINE miraculous things at the twilight of the sixth day of creation. Those things are all things that will make or be miracles in the rest of the Torah: the rainbow, Bilam’s donkey, the pit that swallowed Korah, manna, the well that accompanied the Israelites in the desert, the staff of Moshe, letters, writing, the tablets. There are other rabbis that add other things to this list, but the idea behind is the same: as creation happens, God makes sure to insiert at the last minute all things that will be needed later.

In a sense, there is nothing new under heaven, as Kohelet says. What is new is our eyes to appreciate and to see the miracles that are already there. In that sense, as we read in Maimonides, creation has a set of springs, ready to deploy when the right times for the miracle happens. So miracles are not haphazard moments, but things that were there just to happen at the precise moment they are needed. In a sense this can be incredibly comforting: everything we need is already there, we just need to open our eyes to see it.

We have what is needed.

Now the voices of our reading are connected by a mimdrash found in the Talmud, with another set of voices, found in Jeremiah 33, and popularized by Shlomo Carlbach: kol sason vekol simcha, kol hatan vekol kalah – the verse continues: ko omrim hodu ki tov ki leolam hasdo. What to make of that?

I think it is a reminder to all of us that with listening to God’s voice, to God’s loving invitation to be in relationship with our Creator and our tradition, we are also needed to make others happy. To make others rejoice. To rejoice and be content ourselves: we have all that we need to support each other and the planet in this journey called Life. Let’s use this, all our powers, already in us and in nature, to truly make the world a place worthy of God’s presence.

Shabbat Shalom

Thoughts on the parsha ~ Shemot

Shemot

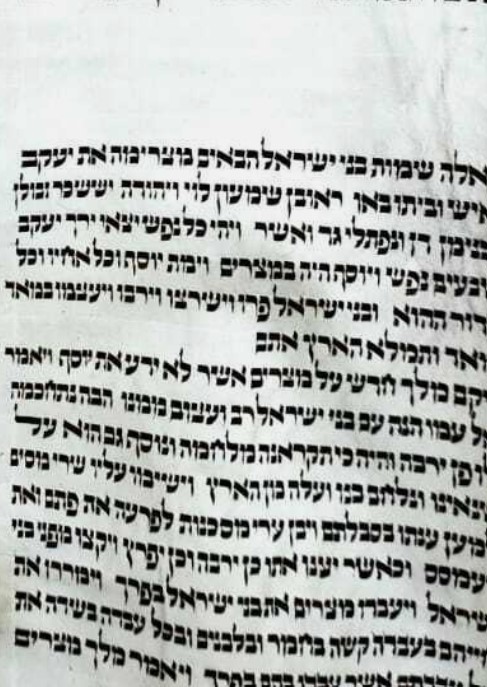

Summary: The name of our portion is Shemot, which means “names”, and it is the beginning of the book of Shemot, or Exodus, in English. In terms of the arch of the story, we begin around 400 years after Yosef is arrives in Egypt, not only with the enslavement of the Jews but with the birth and rescuing of Moshe. The narrative will focus on Moshe and his development, to the age of 80, when he encounters the Holy One at the burning bush, and goes to Pharaoh to demand the release of the slaves. The portion ends with things getting worse before getting better, and Pharaoh forcing the slaves to collect straw to make bricks, while demanding the same amount of bricks.

==

KS – Names and Identity – Moshe

Our portion opens with the names of the sons of yaakov, but the text is already pointing out that there are people not named: we have the sentence saying “70 people came down to Egypt” while the names given are only 12.

Even Pharaoh is not named, and not even called Pharaoh at the beginning, but called “king”. The anonymity extends to all the courtiers of Pharaoh and all the maids of the daughter of Pharaoh, and of course to the slaves. People who will be the movers and shakers of the story – the mother, the father, the sister of the unnamed child who will eventually be named Moshe, as well as his savior, the daughter of Pharaoh, are all unnamed.

IN that sea of unnamed people, only two names will appear, and they are Shifra and Pu’ah, the midwives that dare to defy Pharaoh – the etxt appears to be raising women as leaders, and we will see that through the book of Exodus. But I want to call our attention to the question of the lack of names.

Even the name Moshe, Moses, is not a name in the Egyptian language – mss // child of / son of / Ramses, Tutmses as examples. The text gives a Hebrew etymology for his name, and many people point out the oddity to have Pharaoh’s daughter naming a child and giving him a Hebrew etymology. The lesson that applies to the character of Moses is that he is straddling two identities: Hebrew and Egyptian.

The identity of Moshe will be quite complicated: he goes out and sees his brethren, defends one by killing an Egyptian taskmaster, so he has some of the identity of a Hebrew. The next day, however, he sees two of his brethren fighting – and is rejected, being sent back to the identity of an Egyptian – just to have that taken away from him as well, with Pharaoh wanting to mete out capital punishment to him for killing the Egyptian taskmaster. He runs away – and the daughters of Yitro will say to their father that an Egyptian saved them. And once he runs away, to Midian, he becomes a Midianite – marrying Tzipporah, being quite content with his sheep and his children. At age 80, however, we know things will again change at the burning bush. When God meets Moses at the burning bush, the question of identity is implied in that encounter since God introduces Godself as “God of your ancestors” – which ancestors?

It bears noting that in the story of the Exodus, Moshe is the only Jew who knows what it means to be a free person, but he does not know what it means to be a Jew, and all those who know what it means to be Jew do not know what it means to be free.

In the text, we see Moshe skirting God’s call five different times. The first one is very telling: Who am I to go to Pharaoh? The question could stop in: But who am I?

The five times are also an indication of all the tensions within Moshe: the question of identity, lack of relationship with God, lack of relationship with the Jewish people as a whole (they will not trust me), lack of ability to speak, and just please, please find someone else.

It is not so different with us. We, just as Moshe, carry many different identities. American and Jewish are just two of the most glaring ones, but we have plenty smaller identities. Moshe also has an identity of being disonnected to God and the people, and an identity of disability. And God will not so gently push Moshe beyond those self-doubts and those fractured identities to an identity of someone who can do this. It is not so much that Moshe choses his Hebrew identity, but that he is able to understand himself as able to hold on to all those identities and not be pidgeonholed by any one of them. It is only when he moves to accept that yes, this is who he is, that he can move forward in the service of God. And so it is with us – once we can synthetize our many identities, then we too can move forward.

Shabbat shalom.

==

Shabbat morning

Our triennial focuses solely on the scene at the burning bush. How many times does God need to convince Moshe? Why do you think that Moshe is so unwilling to do what God is asking?

In your opinion, is Moshe different than others, and so that is why God is chosing him? Or is Moshe just a guy passing near a burning bush, and he happens to be in the right place at the right time?

Building a house – Elul 5784

The month of Elul is here. And for the haftarah of Rosh Chodesh, we read Isaiah 66:1 –

The heaven is My throne

And the earth is My footstool:

Where could you build a house for Me,

What place could serve as My abode?

Click here to know more: https://www.gofundme.com/f/build-a-house-for-8-orphans-in-uganda

I have had a relationship both with the kids and Jonathan, via Zoom. I accompany their school work and their health, and I am in contact with the head of the school as well. So if you have any doubts about the veracity of this project, contact me and I can show you all the receipts, report cards and so on.

Thank you for your donation!

Powerpoint for Amos

Download the Powerpoint by clicking here: The Prophecies of Amos

As a way of introducing Amos to the kids of Hebrew School, I made this Powerpoint. It was used to accompany an “interview”. The interview was an activity that involved the kids a bit, with answers taped under the seats. Here’s the script for that:

Interviewer: [Makes a welcome such as a talk show host would] So, Amos, you have been quite in the news, recently! You made a big splash when King Jeroboam the second – remember, viewers, he is the second king name Jeroboam! Our great and mighty king gave a party for all the dignataries of Syria, Philistia, Phoenicia, Edom, Ammon and Moab! And you, a little prophet, crashed that party! Why? That is what everyone wants to know! But I want to know you, before we talk about that! Who are you? Where did you come from?

Amos: It’s not easy to be a prophet. I did not want this job at all! My name means burdened. I am burdened with my visions! My burden is being a prophet and having to speak publicly the words of God! I was a shepherd. Actually, my biggest fear used to be public speaking… I loved being in silence. I worked alone, sometimes with other quiet folk. My sheep were small and speckled, hardy breed to survive the wilderness near Tekoa, where I was born. Let me show you and our viewers some pictures [Fires up Powerpoint] I also dressed sycamore trees..

Interviewer: And what is that?

Amos: You might not know, being a bigshot and all, but that is what poor people like me eat. The sycamore tree makes a very bitter fig. A dresser of sycamore trees needs to puncture the ripened fig to get the bitter juice coming out, and then to be able to make the dried fig into a flour. This is our bread.

Interviewer: Really? I had no idea… I never knew that poor people struggled that much.

Amos: Let me guess. You have a bed made of ivory, don’t you?

Interviewer: Yes… what’s wrong with that?

Amos: even the children of Adath Israel know how people get ivory! Who can educated this man?

Child: [Answers or reads: Ivory is teeth from elephants, their tusks. To get ivory you have to make the elephant feel a lot of pain, is like pulling your teeth out. People kill elephants just for ivory. It is very cruel.]

Interviewer: It is true that my bed was extremely expensive. But I had no idea… [Smiling] But let’s get back to you! You are from Tekoa, you used to be a shepherd of small flock, and made flour from figs. How did you become a prophet?

Amos: I was taking my sheep to graze, and it was midday. You know how hot it can get. I was looking for a sycamore tree to get the sheep to rest under its shade, but suddenly the sheep stopped and would not move, no matter what I did! Suddenly, I heard this voice, coming from the tree!

Interviewer: [getting up all excited] Are you kidding me? A tree that speaks?! I want to go there! I will worship this tree!

Amos: Don’t be a dunce! Sit down! It was Ad-nai! God! Hashem! God was speaking! The tree was just the meeting point! We, Jews, don’t worship trees! Or idols! Any how, the voice of God said: “Amos! Go prophesy to My people Israel! They have strayed far from Me! They are pursuing the gods of corruption and greed!”

Interviewer: But I don’t know what those words mean! Is there a wise child that can tell me?

Child 1: Greed – Greed is an intense and selfish desire for something, especially wealth, power, or things. A greedy person is also materialistic and grabby.

Child 2: Corruption – Corruption is using people in power to get something for a specific person. It usually involves bribery, which are illegal gifts of money, to make the people in power to act or make a law in a way that will benefit the person who gave them the money.

Interviewer: But how can corruption and greed be gods?

Amos: It’s not easy to be a prophet. I did not want this job at all! So much explaining! Greed and corruption become gods when people forget the laws of the Torah! When people use their power against the poor and the weak in a society. [increasingly agitated] When the poor have to pay more taxes than the rich, so that the rich will become more rich, that is corruption and greed. When the poor have to eat bread made from sycamore figs while the rich lie in ivory beds, that is corruption and greed! People are forgetting that the Torah tells us that we have to take care of the orphan, the widow, the poor! A Jewish society is to be a just society, where everyone has the same laws, and rights, and chances to be the best they can! Everyone should be able to eat three meals a day! Everyone should be able to sleep in a house, protected from cold and heat! Every child should be able to go to school! When those things don’t happen, that is because corruption and greed have taken over a society!

Interviewer: calm down, no need to be so excited!

Amos: No need to be excited?! Do you know what I see? I see people being exiled from our land! I see the Temple being destroyed! If we do not change our society, and do right by all our citizens, our people will suffer the consequences! God does not like we have been doing! And God does not like what other peoples have been doing! That is why I, in my poor, coarse, robes of shepherd, had to crash that party!

Interviewer: So now let’s get to the main point of our conversation. Why did you crash that party? [derisively, smirking] And why did you not wear a better robe than your shepherd’s robe?

Amos: Because I had to deliver the messages of Hashem! God had messages to all those kingdoms! And I didn’t care that people were looking at me funny. I know who I am! I am a shepherd. I am a Jew! I obey the Torah! I speak for the poor. The robe I have is the robe I have! The sandals I have are the sandals I have! I became a prophet because God said so. But let me tell you and all our viewers the messages! [Fires up Powerpoint, reads animatedly]

And let us say “amen”!

Interviewer ends with thanking Amos and opening a Q&A.

Miketz – Chanukah day 6 – Rosh Chodesh – Chag HaBanot / Eid El Bana’at

Summary of the Torah portion Miketz – we read about the rise of Yosef and the economic re-structuring of Egypt, transforming the Egyptian people in serfs to Pharaoh. The portion ends in the middle of the confrontation between Yosef and his brothers, when the brothers come for the second time, bringing Benjamin with them.

Today is Chanukah, the sixth day, and it is also Rosh Chodesh. Those are the famous holidays. You might not know but the Jewish communities in Tunisia, along with the communities of Libya, Algeria, Kushta, Morocco and Thessaloniki, celebrated in the Middle Ages another holiday today, called chag haBanot in Hebrew, or Eid El Bana’at in Judeo-Arabic. In English we would call it Holiday of the Women or Women’s Day.

The celebrations varied according to each community, but the theme is the same: connections.

Women would celebrate their connections with each other and their connection with Judaism, God and the Torah. In Israel nowadays, where an effort is happening to rediscover and strengthen that holiday among other holidyas brought by the Diaspora to Israel, researchers of the group HaLuz HaYivri asked questions to those who celebrated the Hag HaBanot in their communities – click here for more. We hear of women going to the synagogue to kiss or touch the Torah, and saying various blessings. Women would get together and cook a meal which they would then celebrate with singing and dancing without the presence of men; mothers would give their daughters gifts and bridegrooms would give gifts to their brides; women or girls who had fallen out with each other would reconcile their differences and pledge friendship to each other. All of these were among the traditions celebrated in the North African communities.

Now, one of the questions that you might have is why precisely today, which is the day that connects Chanukah and a Rosh Chodesh, should be the day for that particular celebration. The fact is that the Maccabees are just one of the stories of Chanukah. There are three other stories that populate Chanukah, each with a woman in the center, each reflecting a different aspect of Jewish tradition and women’s lives.

For centuries, the best known was the narrative of Hannah and her seven sons, which, like the Maccabee saga, appears in the Apocrypha (works not included in the canon of the Hebrew Bible). Hers is a familiar story in Jewish history, one of suffering and martyrdom, and she plays the familiar woman’s role of a strong and pious mother. In this case her strength and piety are put to the ultimate test as the cruel Antiochus, Seleucid king of Syria, tries to force each of her sons to eat pork. As each refuses, he is tortured and murdered while his mother looks on. The king urges Hannah to persuade her remaining youngest son to save his life by eating the pork. Instead, she encourages him to follow his brothers’ example and martyr himself. Torn by grief, with her sons gone, she dies also. Hannah’s commitment to Jewish law under the direst circumstances encouraged generations of Jews in many lands as they faced pogroms and persecutions. Her story is in the seventh chapter of the Book of Maccabees, and you can read it by clicking here.

A very different Hannah takes center stage in a second Chanukah story, generally told in books of legends such as Otzar Midrashim. This is a young Hannah, sister of the Maccabees, and about to be married. Determined to prevent the local Syrian ruler from exercising his “droit de seigneur,” the right to have sexual relations with a new bride, she strips naked before the guests at her wedding feast. When her brothers threaten to kill her because of her shameful behavior, she demands that they save the honor of all Jewish women by fighting the Syrians. As the tale goes, her action sparks their rebellion.

Then there is the story of Judith. In this narrative, Holofernes, an Assyrian general, sets out to conquer Judea, but is stopped by the people of Bethulia (possibly Jerusalem). He besieges the city, and, worn down by hunger and thirst, the elders decide to surrender. Enter Judith. The beautiful widow berates the leaders for their lack of faith and devises her own plan. Taking her maid and a sack of food to eat (she observes Jewish dietary laws), she talks her way into Holofernes’ camp. There she convinces the general that she deserted her people, and by praying to God she can bring him victory. For three days, she leaves in the nighttime to pray, and returns in the morning, thus accustoming the guards to her coming and going. On the fourth day, Holofernes gives a banquet in her honor. Overcome by lust and planning to seduce her, he dismisses his servants, then drinks himself into a stupor. Judith grabs his sword and with all her might hacks off his head. She and her maid leave, this time with Holofernes’ head in their sack. After discovering his headless body, the Assyrian army flees in  disarray, and the Jews win a great victory, “by a woman’s hand.”

disarray, and the Jews win a great victory, “by a woman’s hand.”

So it makes sense that this Woman’s Day would be celebrated precisely when these two moments of the calendat appear, Rosh Chodesh – which is celebrated by women – and Chanukah.

In recent years there have been some attempts made to renew and to strengthen Chag HaBanot, as a push to have a traditional framework for the idea of equality between men and women, which is a part of Israeli consciousness but that has been chipped away by the Rabbanut, with the Sephardi Chief Rabbi in 2019 forbidding women to light Chanukah candles at the Kotel, even in the women’s side of it, and some groups opposing women appearing in photos of newspapers or ads. Groups like the Shalom Hartman Institute have been highlighting this tendency in the past few years. But knowing and celebrating these other holidays is also a way of highlighting the diversity and richness of our people and our traditions, reminding us that we are, at the center, one people with many different facets.

As we continue lighting the candles for Chanukah, may we focus on moving towards a richer and more egalitarian Judaism in our lives.

Shabbat Shalom.

Vayeshev and Chanukah 2022

Summary: We begin the cycle of Yosef, and this cycle takes over the rest of the book of Genesis.

Yaakov settles (vayeshev) with all his family and is clear about his preference for Yosef. Yosef has dreams of greatness, his brothers are envious and plot to kill him, but end up selling him into slavery. The brothers dip Yosef’s special coat in the blood of a goat and show it to their father, leading him to believe that his most beloved son was devoured by a wild beast.Yosef is taken to Egypt and sold to Potiphar and ends up thrown into prison when he refuses to commit adultery with Potifar’s wife. In prison, Yosef meets Pharaoh’s chief butler and chief baker, both incarcerated for offending their royal master. Both have disturbing dreams, which Yosef interprets; in three days, he tells them, the butler will be released and the baker hanged. Yosef asks the butler to intercede on his behalf with Pharaoh. Yosef’s interpretations of the dreams are fulfilled, but the butler forgets all about him and does nothing for him.

==

Chanukah and the story of Yosef are always together, because of the vagaries of the Jewish calendar. In our reading, Yosef has two important dreams, the sheaves and the stars, that correspond to the two dreams of Pharaoh, with cows and ears of grain. But looking at how the Torah describes the four dreams, there is a marked distinction: Pharaoh is drescribed as awakening from the dream, but not Yosef. And so, commentaries abound, some affirming that Yosef was daydreaming and some saying that he was having a prophetic vision. Hold on to that thought.

Now, one of the big questions regarding chanukah is why we celebrate it for 8 days. If the Maccabees found a jug with enough oil to last for one day and the oil lasted for extra seven days, the miracle itself was seven days long. Why then is Chanukah celebrated for eight days?

One answer that is given (by R’ David Halevi z”l, the “Taz”) is that miracles always involve making something-out-of-something (“yesh mee’yesh”), not something-out-of-nothing. For example, we read in II Kings (chapter 4) that the prophet Elisha did a miracle with oil: he made a small amount of oil to fill dozens of jugs in order to save the children of a widow from slavery. She was so poor that the only thing she had was a bit of oil, and so he could cause the oil to “multiply” miraculously.

Similarly, writes the Taz, in order for the oil to “multiply” and last for eight days, there had to be a drop left at the end of the first day. And that is why the mircle in his view is eight days, because there was a bit left, and so the miracle did happen in the first day as well – the miracle of a little bit, of a tad extra. Like hope – there is always a bit left, even in the darkest of moments.

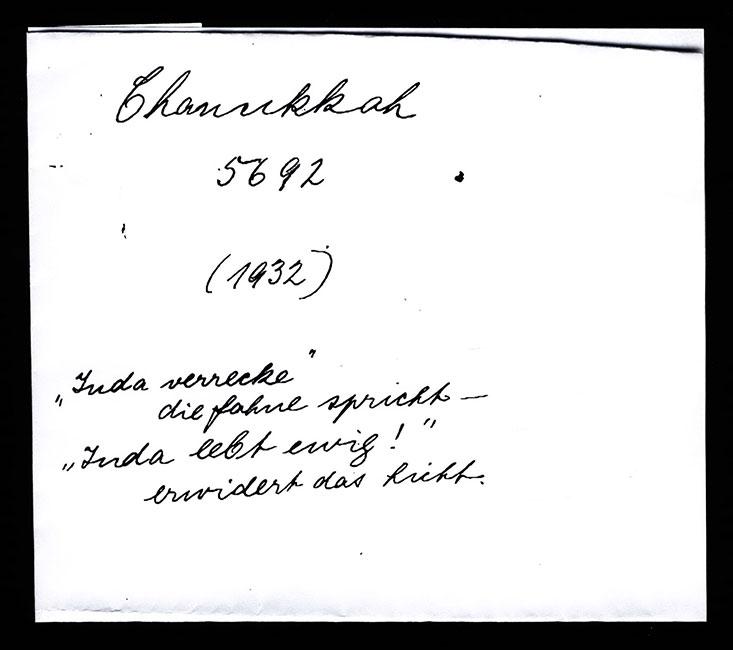

Now look at this picture. By now it’s an iconic picture, and many people have seen it. Yad Vashem distributed it in the internet. It was taken by a woman, Rachel Posner, in a city called Kiel, in Germany, on 1931.

It was an erev Shabbat, the final, eighth day of Chanukah; so the chanukyiah filled with all eight candles and before sundown. It’s framed by the window of an apartment. Just across the way, in the apartment building facing it, unfurled from another window, is the Nazi flag. The two symbols are having a silent conversation. This photo is from 1931; the Nazis hand not yet risen to power, but the threat was acutely felt by the woman, Rachel Posner, who snapped the shot. Her husband, Rabbi Dr. Akiva Posner, was the rabbi of the small town of Kiel.

In looping German script, Rachel Posner writes in the back of the photo: “Chanukah, 5692. ‘Judea dies,’ thus says the banner. ‘Judea will live forever,’ thus respond the lights.”

And so even though it looks like Rachel Posner is dreaming with our people continuing, I want to wager that at times it did not feel like that. Just as Yosef in the pit, or in the prison, was left wondering about his future and hoping beyond hope, so too many Jews after 1933 were left wondering if our people would actually make out of this. But, says the tradition, Yosef was a prophet – and maybe those dreams, dreamed so long ago, gave him hope. Where does Rachel Posner’s hope comes from? I don’t know, but I could guess is an unshakable faith in the Jewish people itself, in our strength, in our resilience.

And today, we too need to answer the question: How do we go on? How do we transmit Judaism to the next generation? What is the power of our Jewish rituals and continuity?

Today we take the Jewish traditions of Torah study, Shabbat and circumcision for granted, but in the context the Maccabees were living in, it was not so. Had they not fought and rebelled, and lived through this miracle, Judaism could have been lost forever.

Our challenges are different than the Maccabees and the Holocaust. But our hope and faith in the Jewish people is the same. And it is up to each of us to light the chanukyiah and find a new mitzvah, a new form to bring light into this world, and do our part – just as the Maccabess did, and just as Rachel Posner did.

And here is a picture of the back of the photo. And a picture of the family as they left Germany in 1933 for Eretz Israel.

Vayishlach ~ Preparations

Vayishlach proposes an interesting change in our ancestor Yaakov (Jacob).

Yaakov has a name that is not really a honorable one. In the two moments when the name is explained to us, readers, the text first points out the need to supplant his brother, clinging to his brother’s heel, and then to the stealing of blessings, as Esav points out that Yaakov actually means yakiv, one who swindles, cheats or sneaks.

We, despite being descendants of Yaakov, call ourselves by the name children of Israel, the name that Yaakov receives in our portion Vayishlach. Yaakov will actually receive this name twice, once by the angel with whom he struggles during the night by the dried riverbed of the river Yavok, and another time when God Godself, using the name E=lohim, will again change Yaakov’s name. But the new name does not stick at all with the first name change proposed by the angel. The text consistently calls him Ya’akov after this. Yisra’el, we are informed, is the one who struggles with humans and God and wins. Ya’akov, the one who cheats.

If we read the entire saga of Yaakov, looking for moments when Yaakov encounters God, we will see that there is a 21 year hiatus – all the time that Yaakov is in Lavan’s house, Yaakov does not mention God at all, using any name. It is as if that wondrous dream of the ladder is put in the backburner, and forgotten. As Yaakov leaves Lavan’s house, stealthy, because he really believes that Lavan won’t let him go, God, using the name Ad-nai, talks to Yaakov, telling him to go back to his father’s house. As Yaakov has his first name change, and then meets Esav and makes peace, Yaakov is still being called Yaakov, God is still being called E-lohim by Yaakov, and things seem to be in a stand still. But then something quite interesting happens: after the whole ordeal with his brother Esav, the text says that God tells Ya’akov to go build an altar.

Ya’akov, from his own initiative, tells everyone in his family that they have to “Rid yourselves of the alien gods in your midst, purify yourselves, and change your clothes. Then we will arise and go to up to Beit El, and I shall make an altar there to the God who answered me on the day of my distress and was with me on the way that I went.”

Ya’akov is preparing to encounter God directly through sacrifice, and at that time sacrifices are what we today would call prayer.

This preparation is essential, at the end: because this is when God Godself will change the name of Ya’akov. The place will also be changed by receiving a new name, since now there is an altar giving a sacred status to that place.

Even though the change in the place is clear, the change in Ya’akov will not be as complete. Yaakov will toggle between the two polar opposites: Ya’akov and Yisra’el. The text will then proceed to show Ya’akov being called by those two names – when Ya’akov is taking charge of the future of the Jewish people, he will be called Yis’rael, otherwise, he will be called Ya’akov.

Yisrael, then is a name connected to expanded consciousness, our higher selves, the version of us that looks in the long run and is able to both ask for forgiveness and forgive, the version of us that shares love freely and is capable of receiving expressions of love. In the end, we want to fulfill Ya’akov’s prayer to God after the dream with the stairs reaching up to heaven: Ad-nai will be our God. So we say every day, twice, the Shemah – Ad-nai Eloheinu, Ad-nai Echad; and in the end of Yom Kippur, Ad-nai hu haE-lohim.

And when we, today, approach prayer, approach this moment of possibly encountering God, we too need to prepare ourselves and be open to the encounter. Rabbi Micki Rosen, z”l, had a saying on the walls of Yakar, the shul I attended when I was in Jerusalem: you can pray in a barn, but can you pray in a barn? The second “you” was underlined. Coming to a space dedicated to prayer is essential to be ready to pray. Our tradition will see choosing what to wear as significant – every time a person changes clothes in the Tanach, in the Bible, that person is either meeting a king or talking to God.

On one level, clothes are an expression of respect. Just as one would not show up to meet a king in rags, one also does not stand before God in prayer in tatters. And yet, in the discussion about what to wear, the halachic decisors will indicate that the clothes do not have to be anything special – they should be clean and presentable. Prayer, as something shared by all, cannot become a fashion show.

What are we to make of all of this once we face realities such as Zoom, and join minyans through our computer? In some sense, we should prepare ourselves as well, and our space. It is challenging to see our living rooms as sacred space, but if we make a conscious effort of preparing the space, it too can become a place for God. If we make a conscious choice regarding clothes, and join the minyan in something other than PJs or sweatpants, we are expressing our readiness to make this experience the best it can be – an encounter with God, an encounter with community and an encounter with the best part of ourselves.

Shabbat Shalom

Ki Tetze – four mitzvot for these days

Summary: Ki Tetze continues the second speech of Moshe. According to the Sefer Hachinuch Ki Tetze contains 74 mitzvot, more than any other parashah, which is 12% of all of the 613 mitzvot in the Torah. Maimonides discounts two mitzvot from that total, and gives us 72. Still a very high percentage.

==

~ Why do we have all these mitzvot at the end of the Torah?

~ How does having all these mitzvot being given disputes the name Deuteronomy, which literally means “the repetition of the law”?

==

As we are approaching Rosh Hashanah I wanted us to notice that in the prayers of RH and YK we ask God to give us life. We will add: Remember us for life, King who wants life, and write us in the book of life, for your sake, Living God.

In Ki Tetze the idea of doing something and have long days appears twice. “והארכת ימים, “and you shall live long days” shows up regarding the mitzvah of removing the mother bird before taking the eggs in Devarim 22. And also למען יאריכו ימיך, “so that you shall live long days” appears regarding having just weights and measures in Devarim 25. Now if you count similar sentences such as למען יאריכון ימיך, and לא תאריכון ימים עליה, so that your days will be long and your days will not be long on the land, you find that this idea appears ten times in the Torah.

On six of those times, the text tells us that if you observe all of God’s mitzvot, you will live long lives. For example, in Devarim chapter 32 (v. 46-47): “And he [=Moses] said to them: pay attention to all the things… which you shall command to your children, to be careful to do all the words of this Torah… and in this, you will live long days on the land, which you are crossing the Jordan to inherit.”

Therefore, we could simply leave thinking that if you observe all the mitzvot, you will live a long life! But that is not realistic, is it? First because it is impossible for one person to observe all the 613 mitzvot – there is no category of individual to whom all the mitzvot apply. All the more so nowadays, when the temple is not standing – of the 248 positive commands, only 126 are currently applicable. And of the 365 negative commands, only 243 are still applicable. The total nowadays is 369 mitzvot.

Even among these 369 mitzvot, however, there are many that most of us will never do since they depend on circumstances. One example is not being tardy to fulfill your vow – only if you make a vow it would applies. Another is building a parapet around the roof of your house – you need to build a house with a flat roof and then have a parapet[1].

But there are four specific mitzvot that the Torah attaches the idea of a long life. Two are found in our parsha. In order of appearance:

The first is honoring one’s parents, as we read in Exodus 20:11 and Deuteronomy 5:16:“Honor your father and your mother so that you should live long days on the land which the Lord your God is giving you.”

The second one is tza’ar ba’alei hayyim, “having mercy on living creatures,” which we find in this week’s parashah (Deut. 22:6-7): “If you happen to come upon a bird’s nest… you shall not take the mother with the fledglings. You shall send away the mother, and then you can take the fledglings so that it should be good for you, and you shall live many days.”

Number 3, is honesty in business, as epitomized by eifat tzedek, accurate weights and measures, as we also read in this week’s parashah (Deut. 25:15): “You must have complete and just weights and measures, so that you should live long days on the land which Adnai your God is giving you.”

Finally, in next week’s portion we read a general instruction: do not engage in idol worship (Devarim 30:17-18) “And if you bow down to those other gods and worship them… you shall not live long days on the land which you are crossing the Jordan to inherit.”

Now, I want to stress that this is not necessarily a promise to the individual. In fact, according to the story in the Talmud, Kiddushin 39b, believing that there is a direct individual connection between observing mitzvot and a long life is what made Elisha Ben Abuya a heretic. The Talmud reinforces this by saying that the long-life promise has to do with the world to come.

Rationalist rabbis nowadays, who do not want us to do mitzvot because of such promises, note that most of those promises are written in the plural “you”. This is pointed out by Avraham Ibn Ezra (Spain, 12th century) in his commentary on the our verse about accurate weights and measures. He says: “For it is well-known: for every just kingdom shall stand, for Tzedek [righteousness] is like a building, and if it’s twisted it’s like destruction — in a moment, the wall will fall.” So rationalist rabbis point out that each individual has the responsibility for the collective. If the collective Jewish people, believes in God, honors parents, deals with money with integrity and honesty, and cares for animals then our collective shall live long days.

Another way to understand this idea, and our request of being written “in the book of Life” is challenging the assumption that long days is a measure of time, or that life means being alive in a body. Doing mitzvot is not supposed to be because you want, as a friend of mine puts it, pie in the sky when you die. You shouldn’t do mitzvot because there is a potential gain with God. You should do them because they are the right thing to do, or as another voice in the midrash says: mitzvot were given to refine us – to make us better people. Abraham Joshua Heschel will say the same: mitzvot are to make us more noble, to discipline and inspire. The book of Life then becomes the book of good life, of a life worth living – and that is above and beyond the actual number of days we have on the planet.

So we can focus on those 4 mitzvot for the next three weeks: honoring parents, being careful with suffering of animals, dealing our finances with integrity and being mindful that there is only one force behind all of existence – God. That is how we have a life worth living, a life that has a long reach in the future.

[1] So, if you look closely to the number of mitzvot, both negative and positive, that we are supposed to keep, that applies to all of us, the number boils down to 270, 48 being positive and 222 being negative.