Rabbi's Blog

RH Day 2 drasha / sermon – the power of being one

I want to thank Adath Israel for the privilege to talk to you tonight. Much has happened since our last Rosh Hashanah together, and I am thankful to have us as a community to process the sadness, madness and miracles of the past year.

A story is told // about a shoemaker // who was a follower of the Rebbe of Ger, Reb Yitzchak Me’ir Alter. The shoemaker// approached the rebbe to know what he could do// about his prayer. “You see, rebbe,” he said, “I am poor. My customers are poor. They only own one pair of shoes. I pick their shoes to fix late at night, when they arrive from work, and I work on them for the night and a part of the morning, so I can deliver the fixed shoes to them before they have to go to work. How should I make my morning prayers? Should I just pray quickly in the morning, rushing, alone, with no intention, so I can go back to work and deliver the shoes? Is that even prayer?”

“What happens, asked Yitzchak Me’ir Alter, “when you can’t pray?” “Oh, rebbe, I raise my hammer every so often and sigh a great sigh, and say “woe is me, I haven’t prayed yet”. “Sometimes”, said the rebbe, “a sigh is more than prayer itself.”

A sigh – more than all the words in the morning prayer, but just sometimes.

And according to Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, “God lives in a word.” But, he added, “Words can only open the door, and we can only weep on the threshold of our incommunicable thirst after the incomprehensible.”

These words of Abraham Joshua Heschel and this story of the shoemaker have been in my mind a lot this past year, since the incomprehensible. I thirst to be able to approach God. And yet.

October 7th weighted heavily througout the year.

And it still does – truthfully I only feel I have got used to the weight, but it is still there, a deep hole of despair and sadness that is reinforced with every hostage that is declared dead, with every interview with a survivor. To be completely transparent, my spiritual survival this year had a lot to do with our daily minyan. To be in community, even if it is to share in the flabbergastedness, even if only to share the heavy news as each day brought details, even if only to say kaddish for countless souls – that was a life saver. Or maybe a spiritual life saver.

And some people asked me – but rabbi how can you pray?

And the question is really not a “how” question. It is not a nuts-and-bolts question. This is a “why” disguised in a “how”.

How can you pray: that is a simple thing – you open your heart and you pour it out to the One that is always listening, even if you are hurt, even if you are angry, even if you are numb and can barely get any feelings out. How is a simple thing: Jews pray with words, most of the time. Either the ones our ancestors honed for the past 2100 years, or your own, or a combination, or a poem you find somewhere – or soetimes, like the shoemaker, Jews pray with a sigh. Tears can be prayer. Or laughter. Or joy.

The how, as I said, is simple – maybe not easy, but simple.

But the question is not a “how”. It is a “why”. Why do you pray, rabbi? Why, in front of such a disaster, do you pray?

The real problem is that we, humans, tend to hide so much of whom we are from other people, that when it comes to talk to God we are in real trouble, as we can’t even show to ourselves who we are – so what does it mean to open our hearts and pray?

And some can say – there is no God, rabbi, wake up, if there was a God, the Holocaust woudn’t have happened! If there was a God, October 7th wouldn’t have happened!

Well, that is not a reason for God not to exist, I’m afraid. There is no reason why God should interfere with what people do to one another, do with one another. The fact is, we are still here.

We, the Jewish people. Through destructions, through expulsions, through pogroms, through massacres, /// here we still stand. If you need a proof of the existence of a miracle, look no further than our own people. The Egyptians? Gone. The Assyrians? Gone. The Babylonians? Gone. The Romans? Gone. But we, our Torah and our prayers? We remain. Ich bin doh, here I am, said the camp survivor visiting Auschwitz 40 years after the liberation. Hineini. Here I am.

When I was at camp Ramah this past summer, one of my classes was with eleven year olds, in which I would discuss theology and God.

Theology is a big scary word, so I changed it to “thoughts about God”. And I explained to them that we need to revisit what we think about God every so often. When you were five or six, I asked, what were your abilities in math? How big were the numbers you could sum? And in English? What kind of sentences did you know how to write? And they all agreed that, if now, at fifth or sixth grade they would present the same work that got them high praise when they were six, there would be no praise. If at age 15 you still think like when you were 10, that’s no badge of honor. Kids know this as “growth mindset” – and what I mean is: we will talk about what you think about God, but do not let this be calcified in your soul, in your heart, in your mind. Let it grow and develop. This is true, just as your growth in language and math is true. You learn, you appreciate, you live more – and you change, and so your relationship with God changes as well.

And then I tell them the story of my grandfather – a wonderful, loving, beloved man who had no use for God whatsoever. I’ll give you the cliffnotes, as some of you may have heard this story before: when I was seven, I flew back to Brasil, seeing my grandfather for the first time in six months. And boy, was I excited to see him. I wanted to share all the wonderful things I had experience flying, all I had seen. He listened patiently, while I was sitting on his lap. And then he asked: but did you see God up there? And I had NO IDEA what he was talking about. That was one of the things that we didn’t do in my house: we did not talk about God. So I asked him what did he mean? And he asked again: well, did you see a man, with a long beard and a scepter, sitting on a throne, up there? And I said no, I had not seen anything like that. To which he replied: this proves to you: God does not exist.

And the funny thing was that already then I did not believe that image of God. And later, of course, I understood – this is an image that every four and five year old has about God. It is the image that the Sumerians had about the gods.

Any Sumerian god is a guy – that goes without saying – ten thousand times more powerful than you, so it makes sense to worship that god and hope he won’t create too many problems for you when he is angry, and hope that he will help you when you need help. That is a fine idea when you are 5 years old and in a concrete phase. You need mental images. But you see – that does not work so well after you are 5 or 6 years old, because life grows, things happen, in my grandfather’s case his father dies, he is left taking care of the family at the age of ten, in a poverty stricken situation so bad that he and his brother had to share one pair of shoes to go to school.

And then, if you are expecting that a supernatural being is going to come and make it all better, because you prayed, you begged, you asked so very well and so very much – I have a bridge to sell you.

That same theology, says Melissa Raphael, in her book The Female Face of God in Auschwitz, which is a comparison of women’s theology and men’s theology, that same theology of an “all powerful god that will come and save you and make his presence known as clear as the day”, that theology enables us to understand how come men, in a much higher percentage than women, went through the holocaust and become atheists. Men, she says, were given a theology of a great power that would intercede and make it all better. A hierarchical theology. God as a strong father who will take care of you if he’s not angry at you.

Women, she says, were given a theology that you find God as you help others in a worse situation than you. A horizontal theology. And do you know how many people in a worse situation than you you can find in a concentration camp?

It is not that God is not there – it is that you have to change your thoughts and your relationship to God, and the way you find God and the way you nurture that relationship and that closeness. To me, that also happens through prayer. Prayer is not about just asking things from God. Prayer is in part a moment that helps me to see who am I becoming, what are my deepest impulses, which ones I wish to curb and which I wish to develop. As I go through the 19 blessings of the daily Amidah, most of which are unabashed requests, I watch my impulses and my words regarding repentance, healing, judgment, peace. Where are my feelings? Where are my desires?

It is said that prayer really is our humble answer to inconceavable surprise of being alive. It is all we can offer in return to the Mystery by which we live. It is a small act – this devotion of mine is wrapped on gratefulness for being alive, able to experience a world that is exquisite in its complexity and beauty, dangerous and marvelous, in which hate and love coexist.

Prayer to me is also a hook my own soul to the chain of our ancestors. The words in the machzor were composed throughout our history, and I tend to use them because in difficult times, like this year in particular, they remind me that no matter how difficult my times look like, there is always a time when it was harder for us, Jews. And yet – hineini, here I am, living in a time when America is still the best of diasporas it can be and Israel is still the best of that the holy land can be.

Rabbi Dr. David Weiss Halivni z”l, a survivor of a labor camp called Wolfsberg, remembers being in the presence of a hazan, Naphtali Stern z”l, who transcribed the High Holiday prayers from memory with a pen, on paper torn from cement bags that he purchased at great risk in exchange for bread. Halivni, then 16, was present while Naphtali Stern led the inmates in the high holiday prayers. Halivni tells us that in the labor camps those who prayed did not create new prayers, the torture and fear silenced the creative urge. Those who prayed, prayed like their usual custom and manner. They sought some traditional prayer that would express their deep longing to overcome the forces arrayed against them, and their sense that the suffering and misery around them was the result of evil, of cosmic forces over which they had no control or influence. Halivni points out that they found such a prayer in the prayer “מְלוֹךְ עַל כׇּל־הָעוֹלָם בִּכְבוֹדֶךָ” (eloheinu v’elohei avotenu m’lokh al kol ha’olam bikhvodekha); “Our God and God of our ancestors, reign over all the world in your full glory…” In this prayer, which you can find in the Uvechen section of our Amidah for Rosh Hashanah, we ask God to reign alone, to take the reins of the universe completely, and not allow evil forces to prevail. Sounds about right, if you ask me.

And also – many new prayers and poems and songs have been composed by Jews since October 7th. For all the terrifying things that this year brought about, both in the diaspora and in Israel, we are still able to be creative.

A rabbi friend of mine went to Catalonia, Spain, and he stood in what was the floor of what was once-upon-a-time a marvelous synagogue. And then he realized – when Jewish people prayed then and there, it was a wholly different Jewish experience. Jews in Spain had arguably the greatest of times in Jewish history – until the ascension of kings who did not like Jews or Judaism at all, and expelled all Jews in 1492. But, even before those kings entered, Jews prayed for centuries in Spain.

And when they prayed towards Jerusalem, it was not to a possible place. Sure, some Jews lived there. But going to Jerusalem, under the Otoman Empire, was not a thing, as they say.

And here we are, almost 600 years later, and if we want we can go – many do, and become part of the strand of our people that make alyiah, return, and experience a Jewish government with a Jewish land with a Jewish army in a Jewish capital. Jerusalem mowadays speaks Hebrew, mostly. And even that is kind of new – the last time we hung out in a Jewish Jerusalem, before the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans, we were speaking Aramaic. But we were still praying in Hebrew.

In our many diasporas, the Jewish people created and absorbed many customs and spoke many languages: Judeo-Arabic, Ladino, Yiddish, Judeo-Malayalam in India, Lishan Didan in Urmia, Yeshivish in present day America and many others. And yet, the Hebrew in the prayer book and in the Mishnah was the great unifier, the one constant in all our diasporas.

But what you thought about God when you said those prayers? No so much of a unifier. A friend of mine in Brasil used to say – the only thing Jews agree on is that there is only One God… and we disagree about everything that follows that statement. And some disagree as to whether that One God exists.

So we are about to spend a few hours together throughout Rosh HaShanah. We will go through the Machzor and we will use some of the new texts in the booklet.

Take this time to refine your relationship with God. To refine your relationship with prayer. To refine your relationship with our people. And if you feel like the shoemaker, if you feel that only a sigh will do, then sigh with all your being. If only tears will do, then cry with all your being. If taking to the streets will do, then take to the streets with all your being.

In times of profound dissonance, in times of feelings of deep vulnerability, in times of deep dislocation, in times of radical disorientation – prayer begins with the machzor, but it does not end there.

Given what year we had, may we make this a better year than last year. LeShanah Tovah, no – let’s say this year LeShanah Yoter Tovah – may we all go on to have a better year.

LeShanah Yoter Tovah.

KN sermon / drashah – We are an incredible people who will survive this

October seventh is a new date for us in the Jewish tradition. It’s a strange thing, this date, as it is now ingrained in our psyches – different from the Yom Kippur war, which began on Yom Kippur, because October seventh is not being called the Simchat Torah pogrom, which could actually be a better description. It is just being called October seventh, as the lack of a title expresses our lack of words – ein milim, there are no words – said every Israeli I know and heard.

And this is not a sermon about Israel or about October 7th, even though it would be easy to give one. It is more than that. Those who know me already know, those who don’t will – I have been an overarchiever all my life. So this is a sermon about us, the Jewish people.

The thing is, I cannot look at October seventh without thinking of the entirety of our people, and the entirety of our history.

In the Torah, as we know, as soon as the Jews leave Egypt, with 10 great miracles, a strong hand, an outstretched arm, seeing God’s greatness and presence become explicit and obvious, in ways that us moderns can beg for and never ever get… …. …. – merely three months later, ‘ninety days’, here are the Jews dancing around // a golden calf. That disappointment leads God to almost kill everyone. Moshe, with words we still chant throughout our High Holidays today, Moshe changes God’s mind. And a few months later, here come the 12 spies. If God was disappointed earlier, now God is really upset. Again wants to kill everyone, and Moshe again is able to prevent that – but, here comes the quicker – that generation has to die. Why?

Put this in perspective for a second: why was God so upset this time around? The Jews were definitely not dancing around a golden calf. They were just afraid, not willing to go up to the land. What’s the big deal?

The thing is… God can deal with you not believing in God. And as modernity continues on, God gets really used to that.

But God cannot deal with you or us not believing in the Jewish people. God can’t deal with you not believing in yourself – after all, God Godself believes in you!

Look it up in any siddur – modeh ani, the very first prayer of the day, ends with us saying “great is Your faith”, Your with a capital Y. God has faith in us as individuals and faith in us as the Jewish people.

So when the Jews say “we can’t do this, we can’t go up to the land, we are mere grasshoppers” – God gets Godly mad.

Now humans are capable of incredible things. Take science, for instance. Some of you know that my parents were scientists, and this frames a lot of my views of reality.

Now what really is the greatest thing in my opinion, is when science mixes itself with another of my interests, history, and yet another one, philosophy. Science nerds all know that there is this amazingly interesting field of History of Science.

Now science, you might be surprised to learn, does not grow incrementally – all science historians know that. Science does not grow neatly, with one discovery on top of the other.

It is not that each scientist discovers something a little more refined or better than the previous scientists, and incrementally we get to truth. That is not how it works.

The historian of science Thomas Kune is the one who writes about this, in his The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

Science, he says, begins with the scientist having a theory about the universe, and theories about how certain things work, and then the scientist and their team gather data points and see if those fit in the theory, refining the theory, giving it more strength. And then, every so often, certain data appear that do not comfirm that specific theory.

And every so often, certain data points bring a complete change – this is what is called a paradigm shift. Take the Ptolomaic universe – this was a theory of the universe that had the earth in the center and everything circling around our earth. It worked until we got telescopes, courtesy of Galileo Galilei. And then you can see, with your own eyes, a moon circling Jupiter.

Oops. Not supposed to see that.

Because that was really the death blow for the Ptolomaic understanding of things.

And this is what happened – the old theory was eventually thrown out, and a new one began forming, one that we call Copernican universe, one that accounts for these new data points. In Kune’s words, this was a paradigm shift.

Tonight I want to venture that our Jewish people knows quite a bit about new data points and paradigm shifts. Despite our fierce love for tradition, and for continuity, our people has adapted countless times, either because of what has happened to us from the outside or because of what we have done to ourselves from within. We recreated, reinvented, reviewed and adapted values, institutions, practices and thoughts.

Arguably the greatest change in our history was the destruction of the Temple by the Assyrians in 586 BCE and then by the Romans in 70 CE.

Each of those destructions brought about changes, by necessity. The first destruction gave us our Hebrew alphabet. And without the temple and its sacrificial system, which were in their last legs due to corruption anyway, we primarily became a people organized around texts, books and the rabbinic interpretations of those texts. Most of you have heard me say a few times that Judaism is not the religion of the Torah, Judaism is the religion of the Torah interpreted, domesticated and renewed by the rabbis – with Mishnah and Talmud, with Midrashim and Kabbalah.

But that was not the only change we survived. The encounter with philosophy, Greek and Arabic, brought us the great Maimonides. It is the obvious tension between that theory of reality and Judaism that impels him, for his own sake and for the sake of his students, to write the law code Mishneh Torah and then the Moreh Nevuchim, the famous Guide for the Perplexed. Who are the perplexed?

Whoever studies both Torah and philosophy, and is perplexed, astounded by the distance between those views, those who are seeing, feeling, understanding this paradigm shift, that do not believe in the same truth of their grandparents.

That shift brings about the Spanish Golden Age, with Jewish music, grammar, philosophy, poetry as our own recreation of our world view and our love for Torah and tradition. And the Jews are very comfortable in Spain for about 6 centuries.

Meanwhile back at the ranch, back in Ashkenaz, we have the Crusades, and Rashi and his grandsons writing their commentaries to Torah and Talmud, 800 years after the mishnah. Another incredible change: instead of knowing things by heart, needing a teacher who knew midrash and could explain things to you, now we have books that can explain things.

Just get a group of Jews together and get going, reading, debating, deciding and revisiting decisions. This was an amazing feat, and Rashi’s commentaries are now the most basic door to understand Judaism.

And then you have the expulsion from Spain. That is another paradigm shift that brings about the first popularization of Kabbalah which takes over the Jewish world. And then the Polish academies and the poverty of the shtetl bring about the Ba’al Shem Tov and all of Hasidism, all the “really Jewish Jews” in the words of a student of mine.

And here is the mind blowing thing: all those amazing books, all those incredible teachers only show up in times of paradigm shifts, in times of discontinuity. It is actually the challenge of discontinuity and destruction that make what we call the Jewish tradition.

Think about it: when everything is ok, when everything is actually going as it should and there is continuity, you just do what your parents and grandparents did. You don’t need a new book if nothing is being challenged. You have no questions. It is all working as it is supposed to. But when the temple is destroyed – we create the synagogues and Yochanan ben Zakai and Yehudah HaNasi together compile the beginnings of the Rabbinic tradition.

And don’t think for a second that any of this happened without despair: as the temple is destroyed, the question is not simply “now, what? Where do we go from here?” The question was much bitter – “does God hate us? Does this all still matter? Where do we go from here?” And come the rabbis to say – Paradigm shift. The word is the center. The study. Open to all. God will be happy with the sacrifices of our lips, with our words. With our hearts.

And here we are, heirs to that break and all the other breaks and despair, and challenges and adaptations since then.

Think of it, we happen to be very good at this.

After the Baal Shem Tov, comes another “small” paradigm shift – Enlightment. The new idea that we, too, are equal citizens like other equal citizens in countries. Enlightment brings the idea that we can do tradition and change, that we can embrace modernity and still be Jews. And new leaders appear. All with profound answers to the question “now, what? Where do we go from here?” As the beloved Hanukkah song says “in every age, a hero or sage came to our aid”.

And October 7th is another such event. It looms large this year and it will loom large for years to come. It has been compared to 9-11, and it has been compared to the destruction of the temple.

And it does not come alone, of course. All our paradigm shifts and all the adaptations I reminded you before, all of those happened with a few centuries between them. But look at the 20th century. That alone brought us [FINGERS] modernity, Zionism, the first World War, the Holocaust, the state of Israel.

It is obvious that we, as the Jewish people, are still trying to figure out what do with modernity. All of the discussions that all the forms of Judaism that we see today, all the facets of this beautiful, great diamond that is the Jewish people – all of them, are answers to modernity’s great question: what is the relationship between the individual autonomous self, and the collective? Between me and my family? Between me and my community, my people, my country, all of humanity, the world?

For us, Jews, that is a huge question. We are still working that out.

We use different facets to do this answering back: Ultra Orthodox, Modern Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, Reconstructionist, Humanistic, Zionist, Secular.

And really, you know and I know that if one of those facets should disappear, the Jewish people would be poorer for it –just as a broken diamond would loose its value.

And let me give you yet another thing to think about: as I said, the greatest destruction that happened to our people in our sources was the destruction of the Temple by the Romans. And the Holocaust makes it look like child’s play. …

And the greatest redemption that happened to our people in our sources was the Exodus from Egypt, and the establishment of Israel in 1948 makes it look like child’s play. …

And the greatest creative center that happened to our people in our sources was Babylonia – and America and Canada make it look like child’s play. …

So all of this – all of those paradigm shifts, all happened in the last two generations. We are still trying to figure all those out.

If you are as old as Rav Yitz Greenberg, may he live to 150, you have seen it all with your own eyes. And some of you around here saw a lot of it.

And then October seventh happened. And I will tell you that I think we all were shaken because that day is revealing fault lines we did not know were there.

The promise of Zionism was that we would not be objects of Jewish history anymore, that we would create a new people and become actors in the history of our people. That Jews would be safe from their enemies at least in our own land. And that shattered.

The promise of America and Canada and the rest of the liberal democracies in the world was that Jews would be accepted as part of the melting pot, or fruit salad. And that shattered: we had to deal with “Jews Will Not Replace Us” in Charlotsville and with “It depends on the Context”.

We, collectively, did not expect that antisemitism would show up in Harvard and Columbia and other universities and colleges. White supremacists were a known quantity, your garden variety of antisemitism, so common that they kind of faded in the background noise of America – until about seven years ago. Those are all small shifts, maybe they are signaling a larger one.

There is one idea I want you to go out tonight with: We have a particular talent for cultural creativity. Our people has an incredible knack for revisiting, translating, surviving crisis and paradigm shifts.

God is not finished with us yet – God has an immense faith not only in you, individually, you, Jew in the Pew, but also God has an incredible faith in us, as the collective of the Jewish people, to keep on going and renewing the connections between us and God Godself.

A dying people does not produce the great things we have been studying and creating and renewing for the past five thousand years. And that we continue to create.

The amount of books and Torah and music and videos and software and podcasts and tshirts and coffee mugs created since October Seventh is staggering.

The German philosopher Theodor Adorno said that writing poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric. As sad as this might be, I want to point out how unJewish that reaction was.

As a response, the Jewish and Israeli poet and educator Rachel Korazim wrote: To write poetry after October 7th is necessary.

As the prophet Jeremiah says: there is hope for your future. Renewing, revisiting and reinventing, creating new traditions, we will get through this – together with our people, taking part in our facet of the invaluable diamond of the Jewish people.

Gmar Chatimah Tovah.

YK day sermon / drashah – Choose life, even when you’re angry at God

There are moments in our lives that clarifies things for us in ways we don’t really expect. And there are people who sometimes cross our paths just to clarify something for us, like a nudge on the right direction – and then they disappear. Like changing a vowel in a Hebrew word, which is a device that the rabbis use often enough, they change how you see things – and whenever you read that verse in the Torah again, it is impossible to forget the new reading.

One example of that is a verse in Song of Songs that states “al ken alamot ahevuha” – and therefore all the young unmarried women love you”. The rabbis say – don’t read alamot, but olamot – worlds. And so the other reading is “and so, many worlds love You”, meaning, You, God, are loved in many worlds, because You are the presence that makes all worlds possible.

So, yes, as one of our great students in Hebrew School would say, Judaism holds by the multiverse theory.

If you don’t know what I’m talking about, my friend Cooper Bruno will explain it to you.

So it is just a vowel – and with that one change, every Passover when we read Song of Songs, I think about maidens and worlds. And there are people, who function in our lives a lot like vowels and the rabbis, giving you a glimpse, changing everything, and then disappearing.

One of those people was the mother // of a guy // I knew briefly in high school. I really did not know him well, we met on our last year of high school and we shared no classes. I am guilty of not remembering his name, or his mother’s. All I remember about him is that he had a brother that everyone thought was his twin, but they were actually born nine months apart.

And for some reason, this kid decided that I had to talk to his mom, whom he deemed very wise and whom he thought could help me. He really set his mind into it – to the point of, on the last day of school, he got his mother to come and, somehow, I found myself sitting in the café near the school talking to this woman whom I never met before – and whom I sensed I’d never meet again. And we talked for a long time. And then she told me that her son said I was interested in Judaism. And did I know what did it mean to be Jewish?

To choose life, she said. I had no idea what she was talking about.

And yes, she was very wise, because then she asked me a question that I only saw again in Rabbinical school.

What happens, she asked, when a wedding procession meets a burial procession in the same street?

Imagine, for a moment, there is only one street they can take. Which one takes precedence?

For a second there, I have to say, I was afraid she wanted to set me up with her son. That’s how clueless I was about this conversation.

But then she continued asking questions: did I know what happens if the father of the bride or the mother of the groom dies just before the wedding?

I had no idea.

Truth is, she continued, the wedding is completed before the burial. And similarly, the procession that takes precedence is the wedding’s, and not the burial. Jews choose life, even when things look bleak. Even when terrible things happen.

Years later, looking back, I am sure that the boy in question just saw my loneliness and my sadness for having lost my father at the beginning of high school, and he sensed somehow that I had spent the two and a half years after that in a mournful stage, stuck. Yes, I went to classes, got good grades, even had boyfriends, but this boy sensed I needed a talk with an adult who would be just invested in helping me out of the rut, the pit, the spiritual and emotional mud I was stuck in.

And his mother did what she could, steering me to look at life, to see life as a blessing to be lived and enjoyed. As the transitory miracle it is. Choose life.

And then of course there’s the verse in the Torah: “see – I set before you life and death, blessing and curse, therefore chose life” – now stop thinking about it for a moment. Isn’t this is somewhat obvious?

If you have life and death in front of you, how could you possibly not choose life? If you have blessing and curse in front of you, isn’t the choice of blessing the one you’d definitely take?

And this is what the mother of that kid told me: no, not obvious at all. You have to be aware that the choice is always there, even in small moments of processions using the same road. Even in large moments of lifecycle events. Always direct yourself towards life – that is where the arrow of the Jewish compass points to.

That conversation returned to my consciousness a few times in the past year. Particularly because we have seen many moments when those two values clashed – death and life. A week after October 7th of 2024, the family of one of the hostages, Itay Chen, z”l, had a dilema: should they go on with the bar mitzvah of Itay’s younger brother?

The Peretz family faced a similar dillema: Should Yonatan go ahead with his wedding, given that one of his brothers might be abducted to Gaza and Yonatan himself had been shot in the leg on October 7th?

The Ben Yishay family had the same dillema: what to do about the bat mitzvah of Noam, when her grandfather, Gadi Moses, is a hostage?

I could go on and on, cases like that were – and to our sorrow, still are – incredibly common. And true to my friend’s mother’s words, true to the Talmud, all of those life affirming moments were celebrated, the absence of their loved ones still there, pervasive, but not setting the tone for the experience.

The barbarity and the cruelty of what happened in October 7th, the scale of the brutality, had a goal which has nothing to do with conquering land: to demoralize and degrade. It was not just about doing unspeakable acts, it was about putting them on the internet for all to see. Because the goal was to shame and humiliate, to transform us, to change our core.

And our collective choice of going ahead, forging the path, of choosing life, is a form of spiritual resistence, a form of spiritual resilience that we can find throughout our history. The decision of not falling into the vortex of despair and anger, the decision of still holding onto limits for actions, even military actions, the embracing of the fact that in two bad choices we must take the one that is less terrible – this is also our spiritual resistance. Because it is always a decision, both for individuals and for the collective.

Choosing life is not always obvious. Many heroes appeared, or were made, by this war. Many were and are soldiers and sergeants, police officers and generals. But soon after the attack, one story captured my attention for days. That is the story of Sholomo Ron z”l. He lived in kibbutz Nahal Oz, which he helped establish. He was 85 years old, and because he was going to have a procedure on Sunday, his two daughters and a grandson were with him that Shabbat. As he heard what was happening around the kibbutz, he made the three of them get into a hidden safe room, despite their protests, and sat on the living room, pretending to read the newspaper. He hoped that the terrorists would assume he was an old man living alone in the house. They did. He knew he could be killed, and he was – saving his family in the process. Had he too hidden himself along with the family, the terrorists would most likely have entered the empty house and searched for the entire family. They would all have been killed, or taken hostage. None in the family were armed, while the terrorists were armed to the teeth with advanced weapons.

Choosing life is not always obvious – sometimes we need to be spiritual contortionists to figure it out. Sometimes we have to think on our feet, get up in our hands and pass our legs above our heads to find the right position.

And I know that there are people who look at today, at Yom Kippur, and wonder – haven’t we suffered enough? What do I have to do with fasting, regretting actions, saying sorry?

And I get it. I get the strength of our collective suffering – here in the Diaspora, we have been reminded almost every day that Jews are seen at best with suspicion by certain groups, at best as useful foils by people who are malicious actors in the cesspool of social media, at best as a problem by people who have difficulty accepting our existence.

I don’t know about you, but I don’t see myself as part of the Jewish problem. I see myself as part of the Jewish existence. I exist. I am not a problem.

And my existence has two poles, the pole of those of us living in the State of Israel and the pole of us living outside of it. It is the existence of Jewish peoplehood.

The rabbis of the Talmud, when confronted with people and animals that had two heads, had a question: are we talking two entities or only one? The solution was, in the best scientific research of the time, proposed as an experiment. Make one head or one side of the body feel pain, and see what happens. If the other side feels pain too, you know it is just one entity.

I felt this teaching keenly this past year – for all our differences, Jews in Israel and Jews in the Diaspora are feeling the same pain. In our incredible multiplicity, in our profound diversity, we are one existence. One people. And together, in the middle of harsh conditions, we still chose life.

The pain, sometimes, seems so great that I know there are some of you who might have arrived to Yom Kippur feeling dislocated and angry, depleted and full of self-righteousness against God, against life. You might feel that you have nothing to apologize for, that God is the one who should be apologizing this year. And to you, I offer the tradition of bringing God to trial, to what is called a Din Torah, or in Yiddish a din Toire.

This was first done by Reb Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev, in Ukraine. It was on Neilah, the end of Yom Kippur – Levi Yitzchak put God on trial. His charge?

That God failed to prevent the persecution and economic deprivation of his fellow Jews of the 18th century – it was really not easy to be a jew in Ukraine in the 18th century. His witnesses? His righteous community, doers of good deeds, mostly poor Jews but not all, and yet all persecuted and beaten in a pogrom. And the verdict? You might be surprised, but this hasidic rebbe, beard and peyes, proclaimed that God was guilty on all the charges. And then… Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev closes his invective by saying Kaddish, the prayer that sanctifies God in the midst of loss and pain, the one you might know from funerals and shiva. His Din Toire is famous, you can find the text in the internet, translated. And Reb Levi Yitzchak finished Neilah, certain that God would bless his community with a good year. In a scene that defies our vision of what a pious person is, Levi Yitzchak chose life, both with lowercase EL and with EL as a capital letter.

Elie Wiesel wrote a similar scene as part of the book Night, and later, his famous play “The Trial of God”. In Night, the inmates in Auschwitz bring God to trial – and Elie Wiesel himself said in an interview that he was there when this happened. At the end of the trial, unlike Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev, who says “guilty”, the inmates said “chayav”, God owes us something, God is in debt. And then they went on to say ma’ariv, the evening prayer.

So the anger and the pain of our existence are made bareable by our choices – by our embracing of the mystery and by our embracing of our collective existence, by our being together throughout the centuries as the miracle we are. Choose life – so that you and your children may live, says the text. So we can live a meaningful, dedicated life to our community, our people and the world.

Gmar Chatimah Tovah.

Re’eh ~ Does God really care what comes into my mouth?

“Re’eh,” means “See”. The texts says “see!! I place before you today a blessing and a curse — the blessing that will come when we fulfill God’s commandments, and the curse if we abandon them. As the Israelites go into the land, says the text, they should put those blessings on Mount Gerizim and Mount Eval. The list of blessings and curses is given in Ki Tavo, along with the procedure. After that, the portion goes onto centralizing worship in the Temple; warnings regarding false prophets, a repetition of the list of kosher and not kosher species, laws regarding the ma’aser, or 10%, to be given to the temple or to the poor, tzedakah, the laws of the shemitah or sabbatical year, and the description of the three festivals in which we would be supposed to go up to the Temple in Jerusalem – Pesach, Shavuot and Sukkot.

==

KS – We are called children of God in our reading, and because of that it is requested of us to observe kashrut, to refrain from eating certain animals and from mixing milk and meat. Sounds funny, if you think of it, to the ears of many non-Jews – and to the ears of many Jews as well.

A friend of mine, Barbara Levitt z”l, was kosher. She told me her experience in a wedding in which she had requested salmon. And an acquaintance of hers, also Jewish, was having some sort of meat. And of course, this lady had to tell Barbara how outdated Barbara was, still clinging to the old ways, God does not care about what you eat! God does not care about what goes into your mouth, jut what comes out! The woman was being so strident, that my friend eventually had to say – I have no idea about God, but you are not being nice at all to me right now.

The midrash affirms that God cares about us and gave us the mitzvot – kashrut specifically – because God cares. Not like an OCD guy, taking notes about what you eat, but about who you become. God cares about that immensely – who are you becoming with your actions? The mitzvot are given to make us better people – particularly food, but not exclusively food. Many of our mitzvot are given to accustom us to kindness.

What is the guiding principle of all the animals you can eat? They are not predators. They don’t tear their food. They don’t become feral. You can have feral cats, feral dogs, wild boars are a menace. But deer? No. Have you ever heard of a feral cow? Even sheep, and we see every so often one which has escaped and been in the wild for years, don’t become feral. In 2021 in Australia one such ram was found, and he had been 5 years in the wild. And he continued to be a sheep. And they took 80 pounds of wool from the poor thing. And he continued to just be a sheep. Sheep, it turns out, do not become feral. You can have wild goats, and wild sheep, but once domesticated, they don’t revert back. And those are the animals you can eat. It is known among breeders of cattle that if a mother rejects a calf, you can always find some other cow that will let it suckle on her.

This is not a trait exclusive to cattle, other animals do that too – the story of the dachshund who raised a pig is so well known that it became a child’s book. But kindness is the basic make up, the Torah says, of the animals you can eat.

The same thing applies to not mixing milk and meat. This is seen as a supreme cruelty: using the liquid that sustained the animal as a way of killing it. The same thing can be said about eating lobsters, that need to be boiled alive, or eating a limb of an animal that is still alive. Those actions are cruel.

The guiding principle, say the rabbis, is kindness. Kosher food should be a reminder, when done right, of the ultimate value of kindness. Eating is something we do every day, we, lucky ones, several times a day. And at every instance we should be reminded – kindness is the point.

Among the many birds we cannot eat is the stork, called hasidah in Hebrew. From that same word comes the word hasid, and the word hesed, lovingkindness. And then, of course, a student asks rabbi Shmelke of Nikolsburg why the stork, the hasida is not kosher. And reb Shmelke says it has to do with hesed. And the student is even more bothered by this – after all, the hasidah, the stork, is known for her devotion and her lovingkindness to her young! To which reb Shmelke says – yes, but she only cares about her own young. The hasidah never extends that love to any other baby bird, never helps others. And that makes the stork not kosher.

So my friend Barbara, who has died recently, was right in her discussion with the lady at the wedding: Barbara herself was a kind woman, always trying to help, always giving a hand to whoever she thought needed one, and the lady, who did not think about what was going into her mouth, apparently was not paying attention on how she was communicating with other people either.

So may this be a week of awareness of what comes into our mouths, and also of what comes out. May we be kind, loving and forgiving to one another. Shabbat shalom.

Re’eh – Love myself a good loophole

Hey Jesse!! It was so wonderful to see you and your parents this past Shabbat. Here’s the notes for the drasha.

==

“Re’eh,” summary:

Re’eh means “See”. The texts says “see!! I place before you today a blessing and a curse — the blessing that will come when we fulfill God’s commandments, and the curse if we abandon them. As the Israelites go into the land, says the text, they should put those blessings on Mount Gerizim and Mount Eval. The list of blessings and curses is given in Ki Tavo, along with the procedure. After that, the portion goes onto centralizing worship in the Temple; warnings regarding false prophets, a repetition of the list of kosher and not kosher species, laws regarding the ma’aser, or 10%, to be given to the temple or to the poor, tzedakah, the laws of the shemitah or sabbatical year, and the description of the three festivals in which we would be supposed to go up to the Temple in Jerusalem – Pesach, Shavuot and Sukkot.

== MORNING

[Please find in our reading which part is most upsetting to you.]

In our reading we come across one of the hardest pieces of the Torah – the laws regarding the ir hanidachat, the city that is supposed to be destroyed. In the reading, the entire city, led by men called “benei belial”. The translations are fascinating: base-fellows, scoundrels, wicked persons, unscrupulous men. In plain English we would call them nogoodniks. Those nogoodniks lead the entire city astray, and after a legal process that includes investigation and research, in which it is found that the entire city is given over to idolatry, you must, says the text, destroy all of it. Not just every person, every building but even every article and every animal. Everything. Nothing can remain.

What are we talking about here, rabbi – I can just hear you ask. And you know what – you should be bothered. How can the Torah say such a thing?! And let me tell you what you already know – the Torah has several laws that make us cringe.

The rabbis in the Talmud certainly are bothered by the ir hanidachat, the destroyed city. And that is not only case that bothers the rabbis, but the case of the rebellious son – we’ll come across that case in parashat Ki tetze – also bothers them. The rabbis then say – nah, the rebellious son never happened. What? If look in the simple Torah text, this is a much easier case to happen – the child just needs to have a bad attitude and drink a sizable amount of wine or eat a sizable amount of meat. I know many mouthy teenagers tha could easily fall in that category. And yet – say the rabbi – this never ever existed.

And here is the secret, which many people tend to look with askance when I point that out – there are loopholes. And I am here to show to you that loopholes are good – when the final goal is love, tolerance and light.

The obligation of humans is to aim for higher moral and religious standards – and I believe we all share this idea. Because people are created in the image of God, our tradition believes we carry within ourselves moral notions of the highest order, which are very close to God’s ultimate will. An individual may not be aware of them, because those notions, that moral instinct, can remain subconscious.

Throughout Jewish history we had moments when we, as a collective, had these moral instincts dormant, or undeveloped. But at a later stage and throughout all of history, these moral notions slowly develop and come to the forefront.

If you look into how the rabbis make the rebellious child never happen, you will find that the rabbis themselves create so many conditions for the application of this law that no wonder it never happened. And they do that because they cannot believe that the text is saying what the simple meaning appears to be.

Here’s an example – according to the Torah text, the father and mother have to say to the beit din “this son of ours does not obey our voices.” The rabbis affirm that this means that they have to have the exact same voice – they have to have the same tone. And they add – it follows they need the same height and appearance. So any child born from a short mother and a tall father or vice-versa will not fall into the rebellious child category.

And of course, the fact that it is a son, excludes all daughters. The fact that is a son, but not an adult, makes the window for this law to be applied a mere six months – between 13 and a day and 13 and a half. And so on, down to the parents’ height and build.

For the destroyed city, our reading, the rabbis do something similar: they argued that it was impossible to destroy the entire city. There is no doubt! Since there must have been mezuzot on the doorposts of some of its inhabitants, you can’t destroy the city.

One mezuzah saves the entire town! You can be a Jewish idol worshipper, but what Jew doesn’t have a mezuzah on their doorpost?!

Talk about a loophole: you all know that it is forbidden to destroy the name of God, which is found in the mezuzah, and if everything in the city had to be utterly destroyed, the law of ir hanidachat could not be enforced and was meant to be purely theoretical.

This is a pretty good loophole. Now – I love this loophole, and I bet you love it too.

Now, let’s be clear here: One could, and just hear me on this, one could take down the mezuzahs. And then destroy the city. Right? You could, and just hear me out on this, kill everything you could kill. But those solutions were something the Sages did not want even to contemplate! They must surely have been aware of these possibilities – I mean, if I can think it, anyone can.

But the rabbis have a different idea. They really believed that God could never have meant this law to be applied. God is a merciful God, called Rahamanah, the Merciful One, in the Talmud. It is present all over the place. It is the most common name for God in the Talmud. So they created a loophole. In order to make sure that the laws that the Merciful one would give are merciful laws, the rabbis found an extremely far-fetched loophole and based their whole argument on a minor detail.

This is yet another way of reminding you – you heard me say this about 100 times since you met me – Judaism is not the religion of the Torah. Judaism is the religion of the Torah as interpreted, domesticated, reframed by the rabbis.

The rabbis could easily have found a more cruel and violent solution, but they chose to solve this in a different way. A way that they actually knew made little sense. It was deliberate trickery, but deliberate trickery rooted in an unequalled moral awareness: the awareness that the Torah is supposed to be a moral conduit, and that mitzvot are supposed to make us better people – not worse. The rabbis believed that the Torah was completely divine – but that is is their task, and our task nowadays, to refine it and to bring it to the moral level that God intended.

The rabbis will do the same thing to all sorts of other laws. One that has been on the news recently is the question of Amalek. There is the case of the biblical commandment to destroy the nation of Amalek and the seven nations of ancient Canaan. Joshua seems to have done something like that, but even he did not do a complete job. In the Mishnah and the Talmud, the Sages found ways to nullify this law and declared it inoperative by claiming that these nations no longer exist. So anyone claiming that Amalek still exists, as a physical existence of a people that needs to be destroyed, is doing an anti-rabbinic reading of the text. That is not Judaism, that is the religion of the Torah.

And I think that we should be proud Jews – proud rabbinic Jews. Jews that look to the Torah, just as the rabbis have for the past 2,100 years, and see Torah as the point of departure, the point of collective growth to be partners with God, to made this world a better place. Torah and mitzvot are here to impels us forward. Shabbat shalom.

Image credit: Synonyms for Loopholes. (2016). Retrieved 2024, August 30, from https://thesaurus.plus/synonyms/loopholes

Ekev – Gratefulness

Ekev is named after its second word which means literally “on the heel of”, i.e. “in consequence of” your obedience. It starts with one of the prominent themes of Devarim, Deuteronomy: whether or not God carries out the covenantal terms depends on the people of Israel. If Israel fulfills their part, they will get the blessings of protection, fertility of body and soil, health and victory. God then draws His people’s attention to their past; the forty years spent in the desert were meant as an educational lesson for them to learn humility, to acknowledge their own relation toward the power of the Almighty and to save them from false pride. Moses reminds his people of their stiff-neckedness, bringing up the example of the Golden Calf episode and stressing his own role as intermediary between God and Israel. A geographic description of the exceptionally good Promised Land, much better than Canaan, follows. The parsha ends with the text in Deuteronomy 11:13-21, which later became the second paragraph of the Shema (“So if you faithfully obey the commands I am giving you today…”).

But today I want us to focus on two verses of our parsha.

- Our texts – Deut. 8:10 and 10:12

| And you shall eat and be satisfied, and bless Adønαi your God for the good land which He has given you. | וְאָכַלְתָּ֖ וְשָׂבָ֑עְתָּ וּבֵֽרַכְתָּ֙ אֶת־ה’ אֱ-לֹהֶ֔יךָ עַל־הָאָ֥רֶץ הַטֹּבָ֖ה אֲשֶׁ֥ר נָֽתַן־לָֽךְ׃ |

| And now, Israel, what does Adønαi your God ask of you, but to fear Adønαi your God, to walk in all His ways, and to love Him, and to serve Adønαi your God with all your heart and with all your soul. | וְעַתָּה֙ יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל מָ֚ה ה’ אֱלֹהֶ֔יךָ שֹׁאֵ֖ל מֵעִמָּ֑ךְ כִּ֣י אִם־לְ֠יִרְאָה אֶת־יְהוָ֨ה אֱלֹהֶ֜יךָ לָלֶ֤כֶת בְּכָל־דְּרָכָיו֙ וּלְאַהֲבָ֣ה אֹת֔וֹ וְלַֽעֲבֹד֙ אֶת־יְהוָ֣ה אֱלֹהֶ֔יךָ בְּכָל־לְבָבְךָ֖ וּבְכָל־נַפְשֶֽׁךָ׃ |

Most of us recognize the first verse from singing the Blessing after meals, and it is the very verse on which the rabbis affirm you should say a blessing after the meals. The second verse is the one that is treated in the Talmud to give birth to a powerful meditative technique offered by our sources: the blessings for before food and for all sorts of events. It is not a joke when the rabbi in Fiddler on the Roof says: wait, there is a blessing for everything.

- Talmud Menachot 43b

| It was taught: R. Meir used to say: “a person is obligated to say one hundred blessings every day, as it is written: And now, Israel, what does Adønαi your God ask of you?” On Shabatot and on Festivals Rav Hiya the son of Rav Avia worked hard to make up this number by the use of spices and delicacies. | תניא היה רבי מאיר אומר חייב אדם לברך מאה ברכות בכל יום שנאמר (דברים י, יב) ועתה ישראל מה ה’ אלהיך שואל מעמך רב חייא בריה דרב אויא בשבתא וביומי טבי טרח וממלי להו באיספרמקי ומגדי |

One hundred brachot every day. That seems quite daunting: to stop and think for one hundred moments in a day. Our current lifestyle does not allow us this luxury – to pause. We run everywhere. We are, for lack of better word, slaves to being busy. But our tradition wants us to remember, every day, that we are actually free. So it gives us the system of saying brachot.

This is a bracha, a blessing: a speed bump in your day. To do it, you have to stop a moment and consider what is in front of you, remember the appropriate blessing, and say it. If you really do embark in this exercise, your entire life will become imbued with a special consciousness – the consciousness of gratefulness. This is particularly true with food, given that we eat a few times a day.

Food writer Michael Pollan is able to summarize all that he learned in his studies about food and humans in seven words: “Eat food, not too much, mostly plants.”

Probably the first two words are most important. “Eat food” means to eat real food – vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and, yes, fish and meat – and to avoid what Pollan calls “edible food-like substances.”

In contrast to this simple idea, however, Western society’s relationship with food is quite dysfunctional.

On one side, we are given the message that we are to take food for granted. Fast food and junk food are examples: eat quickly, and poorly – after all, it is junk, rubbish, garbage. Not real food. For the same price, or a little above, you can have double the portion: and if you can’t eat it all, throw it in the garbage bin. Seeing the amount of food being thrown away in a restaurant is shocking. Having a meal has stopped being a time to sit down, maybe with family, or even alone: it does not deserve its own time in modern society; it is something that happens on the way to work, or sitting in the car. Everything is take-away, portable, and disposable. Not only the packaging, but the content has lost value, too.

Conversely, we also receive the message that food is bad, pernicious and dangerous. Eating disorders abound in both women and men, there are those for whom having a skinny body is the current idol worshipping we do. Counting calories, grams, percentages – food is their main enemy. Also, when overly processed food comes with many additives, reading labels in search for the enemies has become the way many people deal with food.

Michael Pollan, again, sums up our paradox in a very striking way: “The American paradox is we are a people who worry unreasonably about dietary health yet have the worst diet in the world.”

One of the ways to get away from this mentality is to look at what you are eating, and knowing the blessings before you put something in your mouth will help you to analyze what exactly it is: is it food? What kind of food is it? There are basically six blessings for food and drink. If whenever you eat or drink you stop and say a blessing, you are becoming more and more conscious of yourself and the universe around you. If you see yourself saying too many blessings of one type, you know you need to experience more of what life has to offer.

May we find ways to always express our gratefulness to Life, and may every day we find one hundred reasons to do so.

What a trip – Matot Masei

Matot-Masei: what a trip

Summary: The name of the Parshah, “Matot,” means “Tribes,” and it is found in Numbers 30:2. The name of the Parshah, “Masei,” means “Journeys,” and it is found in Numbers 33:1. They are usually read together – the next time they will be read separately will be, bezrat hashem, 2035.

Moses conveys the laws governing the annulment of vows. War is waged against Midian . The tribes of Reuven, Gad and half of the tribe of Menashe ask for the lands east of the Jordan. Moses is initially angered by the request, but subsequently agrees on the condition that they first join, and lead, in Israel’s conquest of the lands west of the Jordan.

The forty-two journeys and encampments of Israel are listed, from the Exodus to their encampment on the plains of Moab across the river from the land of Canaan. The boundaries of the Promised Land are given, and cities of refuge are designated. The daughters of Tzelofchad marry within their tribe of Menashe, so that the estate which they inherit from their father should not pass to the province of another tribe.

KS –

The word Torah is connected to the word horaah, instruction. The idea behind this is that every reading, every verse, every of word and even every letter or lack of it can teahc us something, giving us some instruction. Now the portion of Masei brings 42 stages of the journey of the Israelites, and the question is – what can this teach me, a Jew in the 21st century in America? What does it matter to me thos 42 stages in 40 years in the desert, from Egypt to the Land of Israel?

The word Mitzrayim, Egypt, is related to the Hebrew word metzar , which means a constricted or limiting place, a strait. Both those words come from the word, tzar, narrow.

Mitzrayim can be seen as a moment of constriction in the life of a person. Every person, in his or her life has situations that are a limitation, a constriction, where the person feels that something is preventing growth and expansion. Those situations can be called metzar. In order to get out of this metzar , a person has to exert energy. And when we manage to escape the metzar we get to a place that it is its opposite, the merchav , a wide-open place. Those two words might be familiar to you from the Halel, in which we sing – min hametzar karati Y=h, anani bemerchav Y=h – which means: from the straits I called to Y=h, I was answered by the expansion of Y=h. Think of a moment that you hada problem, recently – when it was over, you might have breathed a sigh of relief: “I’ve gotten out of that tight spot.” Sometimes we can not even be aware of the tightness of the moment, but when it is over you feel “ooooh! Amazing how much better this feels.”

The verses of our portion indicate, according to the Ba’al Shem Tov, what it means to live the lif e of a Jew. It begins at birth, and what follows is a succession of tight spots followed by relief and expansion. Every given time in our lives, in every given stage, we will feel in smaller or greater proportion obstacles and tests. These are the tight spots. The idea is that these situations are to be overcome, and through the process of overcoming them we strengthened. Maybe even our awareness of the loving presence of God is deepened and expanded. What we are not supposed to do is to give up, surrender.

e of a Jew. It begins at birth, and what follows is a succession of tight spots followed by relief and expansion. Every given time in our lives, in every given stage, we will feel in smaller or greater proportion obstacles and tests. These are the tight spots. The idea is that these situations are to be overcome, and through the process of overcoming them we strengthened. Maybe even our awareness of the loving presence of God is deepened and expanded. What we are not supposed to do is to give up, surrender.

In this context, Egypt, Mitzrayim, doesn’t mean a geographical land, a country – the word actually refers to the stages of constriction and development that we all go through on our journey to spiritual development — that utopia, the goal that we follow of becoming more perfect is symbolized by the land of Israel.

Think about your own life and its process. What was difficult at the age of five became almost a joke at the age of ten. What was difficult at the age of ten became a joke at the age of twenty. The difficulties and problems that a young couple faces on the first years of marriage are completely different when they celebrate 20 years of marriage, and yet different when they celebrate 50 years of marriage. Different constrictions come with being a parent and with being grandparents. Every stage in life has its own qualities and challenges. We are contantly being put in new situations, and we have to deal with them and grow through them. Life is a series of metzarim, constricted places and a series of merchavim, expanded places – life is a series of journeys from one to another, and every time you conquered one point, it then becomes a metzar – in comparison to the next stage. As a friend of mine would put it, every time he was telling something difficult that was happening to him, “life is a trip.”

Now, if you are paying attention, this also happens every single day. On any given day, a person goes through journeys from the time we wake up until we goes to sleep. There are days in which waking up and getting out of bed is the hardest thing you can do, and there are days when going to sleep is the hardest thing. Say nothing of avoiding the traps and stumbling blocks in our way.

Prayer, too, works like that – the system itself has stages and levels, and even beginning to davven is a level on its own – just making time, just being disciplined every day. And then there’s the text: we begin trying to make sense of it, we are all intellectual – do we know what the words mean? Can we pronounce them correctly? Are we saying the right words for the right day? But this is all the beginning, and it is quite hard. But once this is conquered and dominated, we get to the next level – paying attention with no distractions: no computer, no radio, not even the distraction of the language. And then we get to yet another level: internalizing prayer. Feeling it. Meaning it. The Baal Shem Tov then says: every word said with the right intention needs a light inside. Your job is to bring the light in. And then, once you are able to get to that point, you move onward to what the Baal Shem Tov calls nullification of the ego. Then, he says, you are no longer in this world, but in Israel, the place where the Divine Presence is revealed. You moved from the constriction to the expansion, going through stages, in davening.

Now listening to all this, you can have the reaction of “why bother? This is impossible!” but then our reading says to you, specifically: chin up! God did not say to go from Egypt, Mitzrayim, to the Merchav, the Land of Israel, in one day! There are 42 stations because we need to appreciate that even if the goal seems far away, the first step of the journey is quite close. You cannot ever compare yourself to anybody else because you don’t know where the other person started from and what their handicaps are. The important thing is to know that you have to keep going. The Torah is saying – just one step. And another. And you will conquer this difficulty, at your own level, at your own speed. Eventually, what is hard today will look easy, and other things will be hard. Different things. And God, as we say every morning, has an enormous faith in us. We can become better people, every day.

Shabbat Shalom

==

Morning:

Morning:

Look at the request of the tribes of Gad, Reuven and half of Menashe, and look at Moshe’s reaction. What jumps out to you?

- Moshe is projecting the past.

- There is an oath.

- The daughters of Tzelofchad, according to the book of Joshua, actually are from the side inside the land, and not Gilead. This makes some look at that story with an eye to a reproach to the rest of the tribe. One of the towns is, incidentally, called by the same name of one of the daughters, Tirtza, and it is in the territory of Menashe inside the land of Israel.

Read morelie = שקר

plank = קרש

Yitro ~ thoughts and actions

Yitro – “Yitro,” is translated as “Jethro”, as in the name of Moshe’s father-in-law. He hears of the great miracles, comes from Midian to the Israelite camp, bringing with him Moses’ wife and two sons. He advises Moses to appoint a hierarchy of magistrates and judges to assist him in the task of governing and administering justice to the people. And then the revelation at Har Sinai, or mount Sinai is described. The famous words – we should be a kingdom of priests and a holy nation. Are said by God, we respond by saying “all that God has spoken, we shall do.” As the revelation is occurring, the people are scared and beg Moshe to receive the Torah and convey it to them. This is one of the few moments when the triennial cycle and the annual cycle have no difference whatsoever, as it would make no sense to read the Aseret HaDibrot only once in three years.

==

Kabbalat Shabbat – important converts

Our reading is famous because of how it is utilized by our Christian neighbors, who are constantly implying that the Ten Sayings are really Ten Commandments, as in THE ten commandments, and there are no other commandments in the Torah. The Jewish tradition respectfully disagrees, and we see the ten sayings as part of a continuous revelation that contains 613 mitzvot, or commands.

The Ten Sayings are called Sayings because they are paired up with different tens, particularly the Ten Sayings that are the basis of the story of Creation. If you go back to Genesis 1, you will find that the words “God Said” appear 10 times. Those 10 times are also connected to the prayer Baruch Sheamar that we say in the morning, in which the word “baruch”, blessed, appears 10 times. In the Jewish mind, all those things are connected in an organic reality, the reality of ten fingers and ten sefirot, in which ten is a number that indicates a basic makeup of the universe.

Our portion has an important characteristic – it is named after a person. There are six parshiot named after people, three non-Jews and three Jews. Noach, Balak and Yitro are the non-Jews, Sarah, Pinchas and Korach are the Jewish ones. But Yitro, Moshe’s father in law, is different than Balak and Noach in which in our very portion, he becomes Jewish. Whereas we do not have really a ceremony for Moshe’s wife Tzippora, there seems to be a ceremony with Yitro. First the translation says that Yitro heard all that had happened to Yisrael from Moshe, then that he was jubilant, then that he says “baruch Ad-nai” and “now I know that Ad-nai is greater than all gods”, he offers sacrifices to Ad-nai and then all the dignitaries of Israel come to eat bread with Yitro.

The word “jubilant” is yached, in Hebrew, that is connected in the midrash with Echad, one. And so of course, say the rabbis, Yitro has joined the Jewish people. It is not just about what he heard – the exodus, according to the plain meaning of the text, or the exodus and the aseret hadibrot, the ten sayings, according to Rashi and the midrash. It is not just that he heard, but that he decides to act on what he hears: he unifies his own experience through the lenses of there being one God, guiding and nurturing and energizing all creation and all creatures.

“Now I know” says Yitro – indicating an arrival. When you talk to converts in general, most of them will express to you this feeling of having come home. Of things finally making sense. Of the experience of exile ending, and a new phase, a moment in their lives that all is connected, and I can see what brought me here, at this moment, even through the darkest periods of my life I see a guiding nurturing force behind it all, lovingly tending to my future.

Jews never think that just a few verses of the Torah get to be more important, and that Torah is reducible to ten verses or even ten actions. Even when Hilel says “what is evil to you do not do to your neighbor” he adds: now go and study. The ten sayings are a portal – and stopping at the portal because you believe that the portal is the castle is to loose the vision of the castle, and forget the existence of a Ruler and a force behind all of it – the path, the portal, the castle.

Yitro, and many others in Tanach, such as Rahav, Rut, the daughter of Pharaoh, Tzipporah, all looked at the entrance and entered into the palace, according to the rabbis. Nowadays, there is an interesting influx of people becoming Jewish, not only in America but worldwide. Entire families, entire communities, go through a process – whether Orthodox, Conservative, Reform – and throw their fate and their future with our people. And the moment they became one of us, two incredible things happen: the collective unconscious gets transferred to them, and they are supposed to be seen like a Jew in all things. Indeed, it is forbidden to remind them of their past, according to the rabbis.

It is not by accident that the portion is named after this character, one who had another religion – if you remember he was described way back as a priest of Midian. And then he joins our people. Yitro is really a stand in for all Jews who have become Jewish after birth, who have chosen the Jewish tradition as home.

May we all merit like them, to choose Judaism as our ethical, moral and spiritual home, seeing with new eyes and a new spirit the story of our lives.

Shabbat Shalom

==

Shabbat morning – eyes for wonder

Count how many times the word “voice” shows up in our reading.

One of the questions of careful readers of our text is how does one understand expressions such as “their saw the voices” at the moment of revelation. Moreover, there are six times when the word “voice” appears in our text, one of those are in the plural, so you could count really seven. One of those voices are of the shofar – and if you recall the extra sentences we say on RH, the shofarot are there, and one of them has to do with the revelation at Sinai.

Now the rabbis in Pirkei Avot say that the shofar that was blown in the revelation moment was from that same ram that Avraham sacrificed in place of Itzchak, AND that particular, metaphysical ram was created together with other NINE miraculous things at the twilight of the sixth day of creation. Those things are all things that will make or be miracles in the rest of the Torah: the rainbow, Bilam’s donkey, the pit that swallowed Korah, manna, the well that accompanied the Israelites in the desert, the staff of Moshe, letters, writing, the tablets. There are other rabbis that add other things to this list, but the idea behind is the same: as creation happens, God makes sure to insiert at the last minute all things that will be needed later.

In a sense, there is nothing new under heaven, as Kohelet says. What is new is our eyes to appreciate and to see the miracles that are already there. In that sense, as we read in Maimonides, creation has a set of springs, ready to deploy when the right times for the miracle happens. So miracles are not haphazard moments, but things that were there just to happen at the precise moment they are needed. In a sense this can be incredibly comforting: everything we need is already there, we just need to open our eyes to see it.

We have what is needed.

Now the voices of our reading are connected by a mimdrash found in the Talmud, with another set of voices, found in Jeremiah 33, and popularized by Shlomo Carlbach: kol sason vekol simcha, kol hatan vekol kalah – the verse continues: ko omrim hodu ki tov ki leolam hasdo. What to make of that?

I think it is a reminder to all of us that with listening to God’s voice, to God’s loving invitation to be in relationship with our Creator and our tradition, we are also needed to make others happy. To make others rejoice. To rejoice and be content ourselves: we have all that we need to support each other and the planet in this journey called Life. Let’s use this, all our powers, already in us and in nature, to truly make the world a place worthy of God’s presence.

Shabbat Shalom

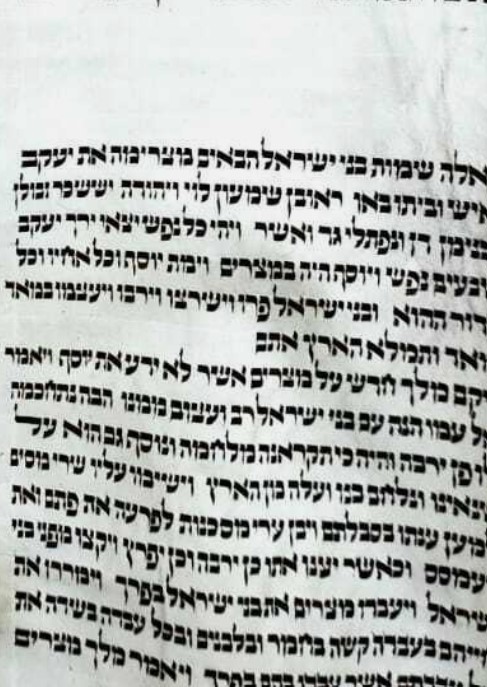

Thoughts on the parsha ~ Shemot

Shemot

Summary: The name of our portion is Shemot, which means “names”, and it is the beginning of the book of Shemot, or Exodus, in English. In terms of the arch of the story, we begin around 400 years after Yosef is arrives in Egypt, not only with the enslavement of the Jews but with the birth and rescuing of Moshe. The narrative will focus on Moshe and his development, to the age of 80, when he encounters the Holy One at the burning bush, and goes to Pharaoh to demand the release of the slaves. The portion ends with things getting worse before getting better, and Pharaoh forcing the slaves to collect straw to make bricks, while demanding the same amount of bricks.

==

KS – Names and Identity – Moshe

Our portion opens with the names of the sons of yaakov, but the text is already pointing out that there are people not named: we have the sentence saying “70 people came down to Egypt” while the names given are only 12.

Even Pharaoh is not named, and not even called Pharaoh at the beginning, but called “king”. The anonymity extends to all the courtiers of Pharaoh and all the maids of the daughter of Pharaoh, and of course to the slaves. People who will be the movers and shakers of the story – the mother, the father, the sister of the unnamed child who will eventually be named Moshe, as well as his savior, the daughter of Pharaoh, are all unnamed.

IN that sea of unnamed people, only two names will appear, and they are Shifra and Pu’ah, the midwives that dare to defy Pharaoh – the etxt appears to be raising women as leaders, and we will see that through the book of Exodus. But I want to call our attention to the question of the lack of names.

Even the name Moshe, Moses, is not a name in the Egyptian language – mss // child of / son of / Ramses, Tutmses as examples. The text gives a Hebrew etymology for his name, and many people point out the oddity to have Pharaoh’s daughter naming a child and giving him a Hebrew etymology. The lesson that applies to the character of Moses is that he is straddling two identities: Hebrew and Egyptian.

The identity of Moshe will be quite complicated: he goes out and sees his brethren, defends one by killing an Egyptian taskmaster, so he has some of the identity of a Hebrew. The next day, however, he sees two of his brethren fighting – and is rejected, being sent back to the identity of an Egyptian – just to have that taken away from him as well, with Pharaoh wanting to mete out capital punishment to him for killing the Egyptian taskmaster. He runs away – and the daughters of Yitro will say to their father that an Egyptian saved them. And once he runs away, to Midian, he becomes a Midianite – marrying Tzipporah, being quite content with his sheep and his children. At age 80, however, we know things will again change at the burning bush. When God meets Moses at the burning bush, the question of identity is implied in that encounter since God introduces Godself as “God of your ancestors” – which ancestors?

It bears noting that in the story of the Exodus, Moshe is the only Jew who knows what it means to be a free person, but he does not know what it means to be a Jew, and all those who know what it means to be Jew do not know what it means to be free.

In the text, we see Moshe skirting God’s call five different times. The first one is very telling: Who am I to go to Pharaoh? The question could stop in: But who am I?