Rabbi's Blog

Eat, my coat, eat

Tetzaveh focuses on the clothes worn by the Kohen Gadol, the high priest. This is a great story – what is the connection to the Torah portion? What values is the story trying to teach?

====

In Turkey, there once was a man who sold coals. His name was Marko. He had a large family, and walked around town selling coals. He was able to sell coals, and with that he eked a living for himself and his family. At the end of every day of work, he would sit on a stone, look at the moon and say:

Dear moon, dear moon, Marko is happy today too.

And he would get up, go home, and feed his family. He had five children, and always arrived in a good mood, making jokes and bringing happiness to his home. It was because he was always with a smile and a good cheer, and always knew how to make conversation flow, that Marko was invited to the weddings and celebrations of the rich people. But he always arrived in his old, tattered coat, and was always smelling of coals. And so he was always sat on the last chair at the very end of the table, and was always served the least appetizing of the burekas and the kubes, the last of the hummus and the hardest meat, the most shriveled of the stuffed grape leaves. But he was happy to come home and be one less mouth to feed, and be able to give a little more to his family.

One day, a rich man to whom Marko sold coals said to him: “Marko, I went to our holy city, Jerusalem, to empty my father’s house. I found this very beautiful coat, and I wanted to give it to you, my dear, because you have sold me coals all my life.” Marko took one look at the coat and knew it was simply not for him. It was beautifully ornamented, made with silk and gold threads, and red dashes and it was amazing and almost unused, if a little old. It had enormous pockets. But the rich man would not take no for an answer. And so Marko eventually took the coat home.

When he got home, his youngest child asked: “Abba, what’s in the bag?” Marko said: “A coat. But it is not for me.” And they all saw it, and all agreed, that coat was for a rich person.

A few weeks later, Marko got invited to another wedding. And as he was about to leave, his youngest child said: “Abba! Go with the beautiful coat this time!! It is better than what you are wearing!” And Marko agreed. He took the coat out of the wardrobe and put it on, pretending he was a prince. He took the broom and pretended to ride it, while showering the “audience” with kisses and weaving. All had a great laugh, and Marko left to the wedding banquet.

As he arrived there, the waiters saw the beautiful coat he was wearing, and put him at the best spot for the best food. All those sitting near him were talking to him about how high taxes were this year, and how it rained too much for the grapevines and too little for the cucumbers. Marko pretended he was interested, but as the food was coming through, he realized it was the best burekas, and kubes, and stuffed grape leaves and salads. And so as he was talking to people, he would stop and fill the pockets, saying: “Eat, my coat, eat!” And all the guests looked at him in amazement.

When he had the pockets of the coat full to the brim with food, Marko thanked the guest, gave a blessing to the bride and groom, and went home. As he did so, he stopped, sat on a rock and said to the moon:

Dear moon, dear moon, Marko is happy today and the coat is happy too.

When he arrived home, his family ate all the delicacies he brought, and that night, they truly had a feast.

Adapted from “Tochal, Me’il, Tochal” by Ronit Chacham and Shirli Vaisman

Tetzaveh ~ the symbols we wear

Exodus 28:31-35 to 29:18 Etz Chayim 508

Haftarah Y’hezkel 43:10-27 520

Tetzaveh continues the instructions given regarding the Tabernacle, with a special focus on the clothes worn by the High Priest.

Both the structure of the Mishkan and the clothing of the kohanim, and particularly the Kohen Gadol are highly symbolic, and one of the ways of finding meaning in these readings, particularly if you are not in the fashion business, is to understand the symbols.

So as I read, please give your attention to the clothes of the High Priest. What do you think they symbolize? I am particularly interested in the first verses of our reading.

===

Our reading deals with certain aspects of Aharon’s clothing: a blue robe with bells, a frontlet, a tunic, a head covering and breeches. The piece our reading skips, because of the triennial cycle, is the breastplate.

==

[A general discussion about clothing and attitudes emerged, with a question regarding “dressing code” for shul. The was a consensus built in the need of it being a internal action much more than a top-to-bottom process. Many shared their upbringing coming to shul wearing special clothing. COVID was mentioned as a time when we don’t pay attention s much to what we wear, and wearing the same house attire everyday contributes to the feeling of isolation]

[Naomi Kamins brought us back to the main topic – the weight is symbolic of the weight of leadership]

And here were my written remarks, which I wove some into our discussion:

First I want us to know that the triennial makes us lose an important refrain, one that appears several times when the Torah is talking about the clothes of Aharon and his sons: lekavod uletifaret – for glory and honor. And the simplest way to understand those is, of course, the saying “the clothes make the person”. We feel differently when we wear certain clothes, and we express our relationship to our surroundings differently. In part this is the game of Purim – we are allowed to wear something completely different and change our relationship with our surroundings as we read that particular story.

Aharon and his sons are expected to take a certain role – the ones who raise the consciousness of the people, despite their own defects. Notice that all these descriptions are coming before what we know is the worse moment of the people, the golden calf incident. So Aharon will wear those clothes with everyone knowing of his own part in the golden calf, and maybe even worse, with him knowing what he did. In a general sense we have this particular set of clothing helping Aharon and his children through what we know today as imposter syndrome, the idea that you are not really good enough for whatever you do, that you don’t trust your own expertise. Aharon, having succumbed to the wishes of the people and facilitating, at least, idolatry, is definitely second-guessing himself at all times. So the refrain “lekavod uletifaret”, to glory and honor – are a validation of yes, you are good enough. Your teshuvah has been accepted – to the point that you and your sons are the priests. That is the most basic understanding.

And now let’s dive deeper.

The blue robe is not any blue – it is tchelet, a specific blue that some nowadays use in the tzitzit. It is symbolic of the sky and the sea, according to the Talmud [Menachot 89a]. Both the sky and the sea are expansion of horizons, a reminder of transcendence, of expanded consciousness of mochin de-gadlut, in the Jewish tradition. Mochin de-gadlut, expanded consciousness, reminds us – and Aharon, of course – that life, to be meaningful, is lived above the constant, small talk of our brains. That talk can be divided into “I like this” “I dislike this”; “this is pleasant/unpleasant.” Mochin degadlut, expanded consciousness, raises above that to try to find meaning. And this is a lesson not only for the kohanim, but also for us. When did you last look to your tallit and desired expanded consciousness? When did you last pray and have a moment of greatness, or at least of greater understanding about your own fights?

Now the Hebrew is interesting here: the blue robe has an opening, a peh, a mouth. Even though it is translated as “opening” the expression is “pi rosho” – the mouth of its head. The text is talking about the robe, but you can read – the Chafetz Chayim (Yisrael Meir Kagan, Belarus, 1838-1933) certainly does – as an indication of your mouth, specifically. And he goes onto marrying the two ideas – transcendence and your mouth. Your words, he says, raise up all the time. So imagine the words you use, when you are happy, angry, sad. When you meet someone. All those words are energies that float up to the Throne of Glory, and there they get separated to confront you later. And so the Chafetz Chayim reads all these descriptions of the robe as warning against the misuse of your own power to speak. For the Chafetz Chayim the moment you abandon the thoughts about how you talk to people you will eventually abandon all mitzvot.

Now, even though Aharon and his sons will be seen as conduits for the relationship between God and the Jews in the desert and while the temple is standing, we all know fights happen. Conflict is inside every single human relationship. How you deal with that conflict is fundamental. The Chafetz Chayim will point out that there is this specific expression on the second verse of our reading, verse 32. The mouth is supposed not to tear, and supposed to be like a coat mail – both of which indicate war. And he says – when you do not feed into the conflict with your own words, that is already a coat mail. That is your defense. So it’s not only about being careful with which words you use, but being careful with how you express yourself, and how you behave in conflict.

Now, what to make of the hem, that has a pomegranate and a bell, all around? There are moments of speech and moments of silence. A bell always makes a sound, the pomegranate never does. Knowing when to be silent and when to speak is fundamental. Speech – because it is energy, because it can build up or tear apart – is partnered with silence, with refraining from speaking. And we could add – with listening. Silence is the first step to be able to listen, and then to hear. And we all want to be heard, particularly by our leaders.

Aharon, in the Jewish tradition, will be connected to the community in ways that Moshe never could be. He runs after peace, making peace between people. When Aharon dies the whole community is upset, the text says “the entire house of Israel wept” – more even than when Moshe dies, when we read “the children of Israel wept”. In part it is because unlike Moshe, Aharon actually listens to people – and tries to work with them. Which is why the next piece of clothing is important.

The frontlet says “Kadosh LYHVH” – Holy to Ad-nai. This is a symbol, a constant reminder to Aharon of his failure in leadership – which is coming in our reading, next week: the Golden Calf. He lets the people build it, does not really take responsibility, and is unable to set limits to the group. If Moshe is all about the rules, decision, limits – Aharon is the soft side of leadership. But it does not end well in that particular instance. So that is the reminder of an eternal struggle of human beings: your core values versus the forces around us and within us. Aharon needs this constant reminder – he is for God. All his work with the community is for a higher value, the molding of this ragtag band of slaves into a more or less cohesive group centered in Jewish values and in God. The headdress, which is like a cook’s hat according to some opinions, or like a kippah, according to others, reminds the wearer of that.

I heard an interesting story – Rabbi Artson, the dean of my rabbinical school, was once a pulpit rabbi. And a teenager came to talk to him. You see, the teenager had began wearing a kippah all the time. But the teen also had a problem, which is, he was a very hot headed driver. He would curse for the drop of a hat, and would cut people off and so on. So his question to rabbi Artson was that, since he felt that he was giving the Jewish people a bad name because of his driving habits, could he just take off the kippah while he was driving? And rabbi Artson said: well, if you yourself know that your behavior while driving is horrifying, maybe the weight of the Jewish people will make you a better driver. No, you may not take your kippah off.

In Aharon’s case the frontlet is there to remind him of his own mistakes, and at the same time to help him as the purifier of the intentions of the people – to take away any sin arising from the sacred donations. That means that as one gives to the Temple – an animal for sacrifice, or the other donations, like first fruits and challah – the intentions and thoughts might need some help. Looking at Aharon with the “holy to Hashem” headband might help also us, simple people, direct our intentions.

And this is, in part, what clothing does. It is supposed to be a reminder of values, something that will help you not buckle under the pressures. There is a famous story in the Talmud (Menachot 44a) about a student of rabbi Hiyya who goes to a prostitute, paying an enormous amount up front, but as he is getting naked his tzitzit slap him on the face, and he decides not to go through with it. The story has a happy ending: she stops being a prostitute, converts and marries him. And it is thought that his attributing a larger consciousness to the fact that he had tzitzit on is what makes for the good end of the story. The moment you wear something specifically with an intent, if you are awake and remind yourself of those values, you will be better equipped to make different choices, more aligned with your best version of yourself.

And finally, the last piece of clothing, the tunic. In Hebrew, it is called kutonet. And there is another story about kutonet – which is the kutonet passim of Yosef. And one Chasidic master, Rabbi Tzvi Elimelech of Dinov (1783-1841) in his book Agra deKalah, connects kutonet that to the sale of Yosef. And to the jealousy that almost destroyed the Jewish people at its very inception. Wearing kutanot, tunics, would help the kohanim to transcend the common jealousies of being siblings and family.

On the word shesh – translated as fine linen – the Alshich (Rabbi Moshe Alshich, 16th century, Tzfat) has his own point. It is not just a reminder of how to guard oneself against jealousy, but also a reminder that Proverbs say that six things are seen as terrible by God – shesh in Hebrew means six. And those six things are pretty basic: lying tongue, hands that shed innocent blood, minds that hatch evil plots, feet who run do to evil, false witnessing, and creating ill-will among siblings.

The Alshich then sees the kutonet shesh, the linen tunic, as a reminder of these six basic things that the kohanim are supposed to be reminded of at all times. The idea being that our leaders are supposed to be held at a higher standard – but also are supposed to have constant reminders of that higher standard.

And so it is with us – it is not just about the kohanim. When did you last make a clear choice about the values you espouse when you use something?

Once I went to a store where kids clothes were being sold – it was a food store – in Danbury. An entire attire for boys – pants, tshirt and shirt – was being sold for 5 dollars. Even though we were strapped for money and my young boys might have benefitted of a new set of clothes, I didn’t buy them. In part because I realized that that price had to come with someone else paying for it: was it slavery? Smuggling? Whatever it was, I decided I did not want to be involved with it. If other people bought it, what could I do? But I was not going to have that in my house.

And I want to let people with that question: when was the last time ou paid attention to what you were supporting when you bought clothes?

May the week that begins bring us to a point of being more deliberate in our expression of our values through our wardrobe choices.

Amen

Shabbat Zachor ~ In(war)d and out(war)d

Shabbat Zachor ~ maftir: Deuteronomy (Ki Tetzei) Maftir 25:17-19

Haftarah I Sh’muel 15:2-34

=====

Today is a special Shabbat, which is Shabbat Zachor. Shabbat Zachor is when we read two specific readings connected to Purim. They are the maftir and the haftarah.

I want to begin by asking you to pay particular attention to the maftir, which is on page 1135 of the Etz Chayim. As I read, I’d invite you to entertain a few questions:

~ To whom is this text speaking?

~ What are we supposed to do?

~ What has Amalek done, and when?

~ Why do we read it just before Purim?

One of the things I want to make sure we understand, and you can see it for yourselves, is what happens before the first encounter of Amalek and the Jewish people. Check page 420 in your Etz Chayim, or Exodus 17:3 to 7 (click here). There what we have is a revolt against Moshe, one of fierce that Moshe believes he’ll be killed at any moment. And just after that, after the text says “the Israelites said: “Is God present among us or not?” – Amalek begins the attack. Hold on to that thought.

Notice that no reason given is given for the attack whatsoever, and notice that the same idea is expressed in our maftir: Amalek attacked those who were most vulnerable. That very same idea will show up when King David encounters Amalek, before he is actually king, in I Samuel 30:1-4 (click here). The Amalekites, just for the fun of it, burn the entire town of Ziklag, where David and his men have settled, and take the women and children captives. The text is pretty clear that Amalek has a certain pattern – it lies in wait for the stronger ones to be distanced or away, and then attacks those who can’t defend themselves, destroying everything in the process.

As some said, we read the maftir because we connect it with Haman, who is called Agagite, and the link between Amalek, Agag and Haman will be explicit when we read the haftarah. There, the king is Agag – and he is the ancestor of Haman.

Now one of the many questions is what moves someone like Haman – and we know that there are Haman’s spiritual descendants, the ones who would have us destroyed – what moves Haman to want to destroy Mordechai’s entire people?

The Talmud takes that question in a by-the-way fashion, as it usually does, when it is discussing whether there are insignificant verses in the Torah – spoiler alert, there aren’t. One of the verses brought up in that discussion is in Genesis 36, among a very long list of the descendants of Esav and other groups. There we read a verse that says “and Lotan’s sister was Timna”. Why would it be there? What can one possibly learn with a verse that mentions a non-Jewish woman in a list of non-Jewish tribal connections not even really connected to the Jews? The answer is brough in a midrash that links another verse about Timna: she is the concubine of Eliphaz, son of Esav. The midrash says – well, Timna, the daughter of non-Jewish kings, wanted to convert and live with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. But they did not accept her as a convert. She eventually does as best as she can, and becomes a concubine to Esav’s son Eliphaz. And who does she give birth to? Amalek, which will become that nation. And so the midrash concludes: and why are we suffering under the hand of Amalek? Because they should have accepted Timna, and did not. The sting of that rejection is what creates Amalek (Sanhedrin 99b click here to read it all).

Does that make ok for Haman to want to destroy us? Of course not. But here the rabbis begin with the midrash a process that will have an important impact on how we read the verses of our maftir: an internalization of Amalek. Amalek stops being a people we have to actually destroy and becomes a force, something that exists in the world – and within us. And to clear out Amalek, we need to first clear out our internal Amalek. The rabbis of the Talmud are worried about dismissing potential converts, and are incredibly worried about the oppressing of converts, to the point that it will affirm that not oppressing converts appears 36 times in the Torah (Baba Metzia 59b click here).

As this process of internalization continues through our people’s textual history, it does not stop at the question of accepting and treating well those who chose to come under the wings of the Shechinah. It takes on a more general human aspect. The Kedushat Levi (Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev, 18th century Poland) has a very potent explanation of the verse. Amalek is the force within every human being. Since every human is a small world, and since we see that Amalek exists in the world, it follows that it also exists inside us, inside each human being. The Kedushat Levi points out that just before the attack, in Exodus 17, the Jewish people are weak. And we saw this – they bicker and rise against Moshe. That is how we can reread the verses we just did, the middle verse of our own maftir, verse 18:

אֲשֶׁ֨ר קָֽרְךָ֜ בַּדֶּ֗רֶךְ וַיְזַנֵּ֤ב בְּךָ֙ כָּל־הַנֶּחֱשָׁלִ֣ים אַֽחַרֶ֔יךָ וְאַתָּ֖ה עָיֵ֣ף וְיָגֵ֑עַ וְלֹ֥א יָרֵ֖א אֱלֹהִֽים׃

he cooled you off in your pathway, and cut down all the weak ones in your rear, when you were tired and hungry – and then the verse says “and did not fear Elohim”. The verse is not really clear to whom that “did not fear God” belongs. And so, the Kedushat Levi says, the strength of our people, which is Torah and prayer “since the voice is the voice of Jacob” – needs to be there. Because when we let that go, he says, when we don’t feed our awe for God and the world, then Amalek attacks. You can read the explanation of the Kedushat Levi on Sefaria, click here.

The legacy of Amalek, the destructive force, the force that due to greed and anger destroys things sometimes simply for the pleasure of destruction – that is a fight for all times. That is what we have to constantly try to erase, and never forget – because as long as human hearts exist, the temptation of seeing others as mere means to an end will always be there.

So may we have a Purim of giving gifts to the poor, giving gifts of food to each other, reading the Megillah and feasting – but always remembering that all these festivities are to remind us that our internal work continues.

Shabbat Shalom.

Parashat Yitro

One of the few parshiot in which the triennial and the annual readings are the same. The reason is that the 10 commandments or aseret hadibrot, figure in them – we would not imagine having a year in which you don’t read about the revelation at Sinai.

===

Well, and there is the joke about Joe Cohen. His alarm went off and he said the famous words “just five more minutes”. When he woke up he was 30 minutes late for an important meeting. He puts on a suit and runs out the door. He gets stuck in traffic and as he arrives at the company’s parking lot he is still 25 minutes late. He looks for a parking space and finds none. Zilch. Having driven around the lot and checked out each potential space, he stops his car in desperation and looks up towards the heavens. He is not a religious man in the least but he cries out:

“Dear God, if you please just give me a parking spot I promise I will go to synagogue every week, will only eat kosher food, and I’ll follow every single one of the 10 commandments, just PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE give me a vacant spot so that I won’t lose my job!”

Miraculously, a parking spot opens up right by the front of the building. He then looks back up to the heavens and says, “never mind I just found one!”

I love this joke, and a British rabbi, Rabbi Claude Vecht-Wolf, is the one that told that to me.

===

Look at the asaret hadibrot, popularly known as the ten commandments.

~ Why do you think the Jewish tradition does not call these 10 commandments, which would be aseret hamitzvot, but aseret hadibrot, or aseret hadevarim, the ten sayings?

~ Which one is the hardest, in your opinion?

~ How would you categorize or divide the aseret hadibrot? Be creative, there are at least three different ways.

===

So the first thing that I wanted us to notice is that by calling the 10 commandments Aseret Hadibrot our tradition tries to connect them with the story of creation which, if you count, has ten “and God said”. Ten sayings and ten sayings – so there is this message that the entire creation is upheld by those actions or refraining from these specific actions.

This is the easiest way of dividing the Asret Hadevarim – positive and negative.

Another way is “God’s name is mentioned” and “God’s name is not mentioned”.

Another way is “bein Adam Lamakom” – between you and God; and “bein adam lechavero” between you and your fellow human beings.

A way I want us to get familiarized with is how the sage Avraham Ibn Ezra, who was alive in the 11th century in Spain, divides the mitzvot in three groups:

Of the heart, of the tongue and of doing. And then he subdivides these in positive and negative.

Now some are pretty easy, such as murdering and stealing – or at least we imagine so. The most challenging is coveting. Why is it the most challenging? Because we usually do not think that emotions can be regulated. And how does Ibn Ezra understand this specific, thorny commandment?

In the first section regarding the heart, his positive ones include “love God”, the veahavtah et Adnai elohecha” as well as to ‘love your neighbor as yourself’. The negative ones cover such commandments as ‘don’t hate your brother in your heart’ or ‘don’t bear a grudge’.

In the second category regarding words of the tongue, he includes the commandment to say the Shema twice a day and Grace After Meal (‘Benching’) and an example of negative is the not bearing a false witness or cursing using God’s name.

The third category are actions.

So going back to the Aseret Hadibrot, he points out that the first two are of the heart, because if you’d think that not bowing down to idols was an “action”, you’d be wrong – it is an expression of the heart, he says, since it is about loving God. The third commandment is about the tongue, as even if you love God you could use God’s name in vain. Shabbat is about actions, as is honoring parents. Those would be in the first tablet. On the second tablet, he says, what you have is the another set of actions – murder, adultery, stealing followed by not swearing falsely in court, which is obviously a question of how you use your tongue. Which leaves, of course, coveting for the heart. And it looks like a neat sandwich, for sure, but is not exactly helpful.

And of course Ibn Ezra has a response. He says yes, it is a heart business, but not like what you’d think. He brings a parable to explain, and in the parable there is a peasant that sees the daughter of the king. Even though she is beautiful, and the peasant knows that, the peasant will not covet her since it is as possible for him to sleep with her as it is for him to suddenly sprout wings in his back. So for him – and for many other rabbis – coveting is not simply feeling the desire, but trying to actively get what you desire. That is illustrated with two fairly famous stories.

The first one is of none other than King David, who sees Batsheva bathing on the roof, has an affair with her while her husband Uriah is fighting the war with the Philistines, and when she reveals to David that she’s pregnant, David proceeds to kill Uriah. The second story comes from another king, Achab. Achab wants a vineyard that belongs to Navot, and Navot or Naboth, does not want to give it to him. So he does what all great kings do, and pouts, and whines and refuses to eat. Jezebel, his wife, does what all great queens do, and tells him to kill Navot and just stop whining already.

And that, for the rabbis, is the most important thing – it is not about wanting the woman or the vineyard, it is not about fantasizing. It is about using your smarts or your power to get what you fantasize about, even though they are not supposed to be yours in the first place. Ibn Ezra wants you to know an important maxim of the Jewish tradition, which is – certain things are given to you as part of your existence. What possessions will you have, how long your life is and how many children you have are all decided beforehand. So coveting something or someone is really about being ungrateful, and not seeing the blessings you already have in your life.

By seeing “do not covet” as a heart commandment, and by defining coveting as actively trying to get what you cannot have, Ibn Ezra is really trying to tell that coveting means making the plans. The heart is not necessarily the seat of emotions alone, but of all thought. In that sense, controlling coveting really means controlling the thoughts of planning – and not the emotion of desire. It is about controlling the tendencies of being ungrateful – and that even modern psychology says is possible.

So may this week be a week of seeing that our grass is greener than the neighbor’s simply because it is our grass. And may we find the grace of being thankful for the many blessings in our lives, for our internal and external beauties and for our many gifts.

Shabbat Shalom

Bo ~ Choosing to go through the door

The portion begins with the plagues of locusts and darkness, and its bulk is the death of the firstborn and the going out of Egypt.

Bo is the parsha of the Exodus, in the sense that it is here when we read the last night of the Jews in Egypt. It is in Bo that three of the four children, with their questions, appear. “When your children ask: what is the meaning of this for you?”; “When your child asks: what is this?”, and “you shall say to your child”. These are known as the wicked, the simple and the one who does not know what to ask.

Notice that we celebrate Pesach today as one big holiday, but it is actually composed of two, both mentioned in our portion: Chag HaPesach and Chag Hamatzot – the festival of the Passover sacrifice, lasting one day, and the Festival of Matzot, that lasts 7 days.

Our portion makes clear that there are two different Pesachim (plural of Pesach): Pesach Mitzrayim and Pesach LeDorot, that is, the First Passover; and the celebration of Passover for all generations. For instance, we do not smear our doorposts with blood nowadays, but the did that in Egypt.

The image of the Jews painting our doorposts is a fairly famous one. Look at the text – this command is repeated twice. Why do we have to paint the mezuzot with blood? Where do you think this blood is – in the inside or the outside of the door? Who needs to see it, and why?

====

The first thing I want us to notice is the preparation for that moment: the text says – the lamb was to be selected on the tenth of the month, kept separated and guarded, and then slaughtered, roasted and eaten.

According to historians, rams were seen as a symbol of fertility in the Egyptian pantheon and were identified with various gods. Ram-headed sphinxes flank the entrance to the temple of Amun at Thebes. The bodies of some rams were mummified and equipped with gilded masks and even jewelry. So there is quite a statement being made here, which is, we, slaves, will take the symbol of the deity – a one-year old ram – slaughter, roast it, and eat it. The blood will mark our doors. Nachum Sarna affirms that there is a process of making the interior sacred, marking the difference between interior and exterior.

A collection of Midrashim, the Mekhilta deRabbi Yishmael, offers three possibilities:

“(Exodus 12:7) “And they shall place it on the two side posts and on the lintel”: on the inside. You say on the inside, but perhaps on the outside (is meant)? It is, therefore, written (Ibid. 13) “And I will see the blood” — blood which is seen by Me and not by others. These are the words of R. Yishmael. R. Nathan says: On the inside. You say on the inside, but perhaps on the outside? It is, therefore, written (Ibid.) “and the blood will be for you as a sign” — for you and not for others. R. Yitzchak says: On the outside — so that the Egyptians see (their gods being slaughtered), and their insides be “ripped apart!”

The midrashim usually have no problem with presenting different opinions without harmonizing them. Each of these three opinions hold different attitudes. God wants to see the sign – in part because, as the midrash explains next, once the destroyer is out and about there is no distinction between good and bad people. So the destroying force, which is clearly not very bright, needs a sign to do precisely what the term Pesach means – skipping. The third opinion holds that it is an outside sign, but God is not the audience. The audience are the Egyptians, who will see their gods being slaughtered. That is the symbolic act of leaving idolatry.

The second opinion that holds that the sign is for the inside, is the one that interests me more this year. The audience is the Jews themselves.

There is this interesting idea that four things were kept by Jews in Egypt, which was why they were redeemed, but God’s worship was not one of them. There are four things: Jews kept their names, their language, the idea of not speaking lashon hara, and the idea of not being promiscuous. (Vayikra Rabba 32:5 and other places). Which points to another idea, popularized in the 16th century, that we were almost not redeemed, we were steeped in 49 gates of ritual impurity. 50 is the maximum. Those four things – the names, the language, the value of faithfulness and not gossiping are the hook that made it possible for us to get out.

So marking the door has a lot with us choosing to continue the Jewish experience – with us actively choosing to be, not passively being chosen because we are descendants of Avraham, Yitzchak and Yaakov. That idea is not present in the Book of Exodus at all. The escape from Egypt has to do with a promise made to Avraham, and not so much with a choosing that God makes about our people. The idea of choseness comes later, after the giving of the Torah, and our accepting of it. And then the choseness is not unconditional, and does not point to an ineffable essence, but to acts and actions, mitzvot.

And if we think about it, how could God be choosing Jews in Egypt when we did not even know God that well? Remember, the plagues are not just for Pharaoh’s benefit – the plagues surely are an answer to Pharaoh’s question “who is God that I should let Israel go?” – but the plagues are even more a question of teaching the Israelites who God is. Next week, in Beshalach, we will read that once we have seen 10 plagues, once we were at the Sea seeing the Egyptian army drowned, “the Jews believe in God and Moshe”.

We know that a mixed multitude came with us, they saw the possibility of freedom and took it. But we also know that the desire to go back to Egypt will not leave the Jews for forty years. Poor Moshe has no idea yet, but soon he will know. And why we will want to go back? For the menu, the leeks, the cucumbers, the fish, the meat. And you could imagine that there were those who decided to stay behind, who didn’t want to go out. Who liked fish, cucumbers and leeks so much that they thought they were a fair price for freedom. Those did not mark their doors, sealing their fate forever, disappearing from our people –later also forgetting names, language and values.

So I believe that the blood on the door is actually for us, it is our moment to say “I’m in”. The Zohar affirms that at that fateful night in Egypt we are not simply smearing the blood on the frame and the doorposts – we are writing three yuds, one on each piece of the door, and that is the sign. In some old prayerbooks you can still find God’s name portrayed like this. In the Zohar’s imagination, the door is always there – every time you pray. Because as the distance grows between the miracles in Egypt and us we understand much more the nature of the miracle. It is a constant choosing to be Jewish, keep Jewish, act Jewishly. It is as much a miracle of God as it is a miracle of the people: keeping, against all odds, the flame alive.

May we continue to do so this week, keeping the flame, the continuity, the mitzvot, Hebrew.

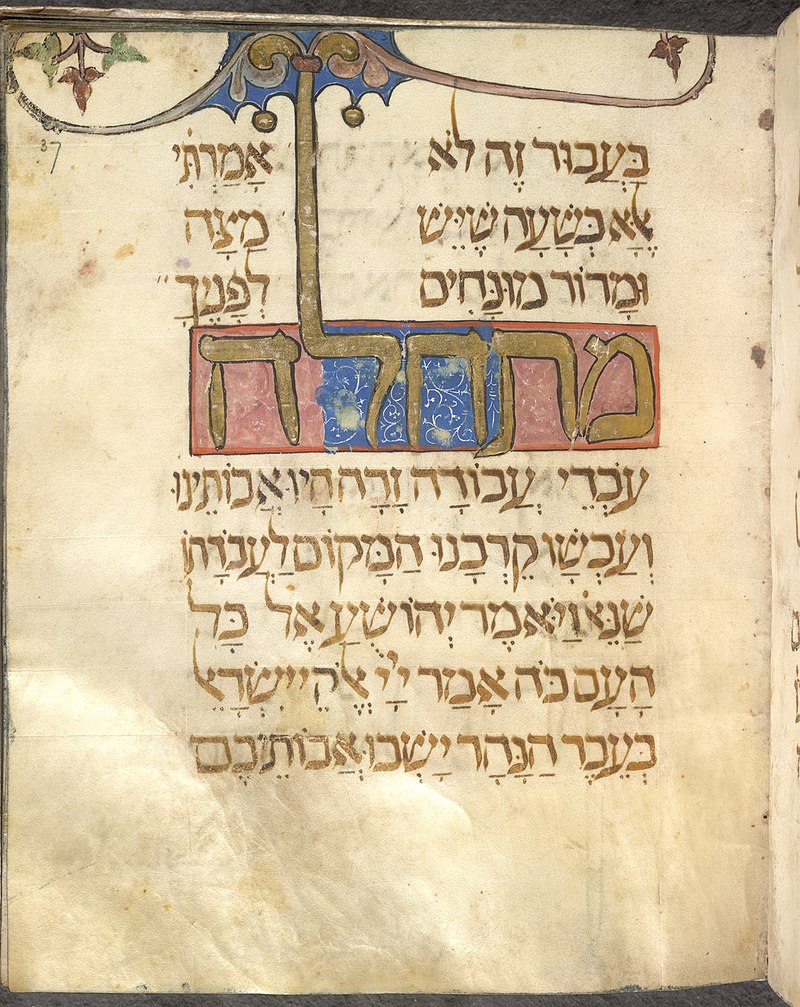

< page for the “Haggadah Hermana” or “the Sister Haggadah” manuscript (Spain, 13th century)

On the attack at the Capitol

Dear friends,

As more and more information becomes available about the storming of the Capitol on Wednesday, not just about the violence, the victims and participants but also about the details of those harrowing hours, I would like to share a few thoughts.

The first one has to do with the images of observant Jews, some in kippot and tzitzit, some in skirts and snoods, participating in this. They were engaging in a demonstration to overturn the government’s basic institutions, a demonstration that had violent ends, proven by the presence of a noose erected outside. One of the most important principles in Jewish Law is Dina DeMalchuta Dina – which means literally, the rule of the land is the rule[1]. We obey the laws of the land. Examples abound: paying taxes, speeding or using banned substances – Jews should obey all those laws, and every other law enacted by the government. All the more so this principle applies to violence.

Dina DeMalchuta Dina is only supposed to be crossed if the government is forcing Jews to stop observing Jewish law. One example would be if the government forbade circumcision – then we keep doing circumcision, even if it means travelling with the infant to a nearby country that permits circumcision, as it is the case with our Kenyan brothers and sisters, who travel to Uganda[2]. But even such a case does not give permission to try to overthrow a government using violence.

The noose outside also hinted at executions, without what we would call a due process, of those considered enemies by the leaders of this mob. In more stark terms, lynching was not outside of the imaginary of those perpetrating loudly the storming the capital, or those supporting it silently. Again, there is no such a thing in Jewish law: even murderers get their day in court. Eichmann did. There was a process, witnesses, defense and prosecution. Lynching has never ever been condoned in Jewish thought and Jewish law.

Let’s talk about violence. And destruction. Destruction of public property has no place in Jewish thought. Cutting fruit trees in times of war is forbidden. Even destruction of your personal property is forbidden, unless there is a higher purpose[3] – an upcycling of the materials: you can dismantle a table to make chairs, or reform a building, or building something. But not as an expression of rage, anger and violence. In the Jewish ethos, even necessary violence, ie, war, has its constraints.

For starters, wars of aggression, which are began to conquer territory, are not permitted nowadays given the lack of a king in Israel, and the fact that the Sanhedrin is not in existence[4]. We are supposed to engage in defensive wars only. Moreover, even in secular terms, the Israeli army in its code of ethics, called “Ruach Tzahal”, affirms the values of human dignity for all humans, purity of arms and democracy[5].

It deeply disturbed me, and I am sure that some of you saw the pictures too: it appears that there were people wearing t-shirts with an acronym 6MWE which stands for ‘6 million wasn’t enough’, it is certain that there were people wearing t-shirts with “Camp Auschwitz.” It strikes me as profoundly naïve that Jews, observant or secular, were hand in hand with people sporting those, as they storm or support storming the seat of the government. Our history has shown that antisemitism finds its breeding ground in extremism, and for those sporting those shirts there are no “good Jews.”

The pictures of an Israeli flag and a confederate flag flying side by side were also upsetting for a similar, complementary reason. Degel Israel, the Israeli flag, was based on a tallit, the symbol of God’s presence. That is the same God that affirms, in Genesis, “let’s make humans in Our image.” Not Jews, not Whites, not Blacks, Asians or Natives. But “humans.” All humans. And the confederate flag stands for the right of reducing certain humans to chattel. The Israeli flag reminds us of our own 2,000-year landlessness. It reminds us of our being vulnerable, of our longing for freedom. It should be a modern articulation of a prophetic promise: that we, all Jews, rose from slavery, exclusion and oppression to champion the values of justice and compassion articulated by the prophets to the entire world.

The attack in the Capitol has been called many names by many people. One that I have not seen yet is desecration, which I think it fits in many levels. The institutions that are “the pride and glory of our country[6]” were desecrated, symbolically, in this attack. Many of the values that we hold dear, because they are the connections between Judaism and America, were desecrated. But above all, core values of Judaism: respect for the rule of law, human dignity, due process, limits to violence, not destroying wantonly, were desecrated, together with our common destiny, were desecrated. Jews, religious or secular, have no place in a destructive and violent mob trying to overthrow seated government.

Warmly,

Rabbi Nelly Altenburger

[1] Nedarim 28a, Gittin 10b, Baba Kamma 113a-b and other places in the Talmud.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Jews_in_Kenya

[3] Maimonides, Sefer Hamitzvot, Negative Commandment 57

[4] Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Melachim 5:1-2. Even if Maimonides accepts the possibility of a war of aggression, notice that he envisions that only in the context of a King being able to convince the 71 judges of the Sanhedrin that this is warranted.

[5] https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/ruach-tzahal-idf-code-of-ethics

[6] Prayer for Our Country

1/10/2021

Vayishlach ~ What happened to Dinah?

Vayishlach is a packed portion, mostly focusing on Yaakov and his road to redemption from being Yaakov to becoming Yisrael. The portion opens with Ya’akov sending messengers to Esav, their encounter and their settling things out. It is in this story that Ya’akov has his struggle with the angel, and is named Yisrael for the first time. Deborah, Rivkah’s nurse, dies. Rachel also dies, giving birth to Benjamin. The portion closes with the line of Esav.

Our triennial focuses on the story of Dinah, which happens just before the deaths of Deborah and Rachel.

As we read the story, I’d like you to think about a few questions:

- Using the text, describe Dina with your own words. What do you imagine is going to be the traditional understanding of Dina?

- If this is a case of rape, what is missing? Could you read this as a case of seduction? What does the simple meaning (pshat) imply regarding Dina’s agency?

- What do you think of Shechem and his actions? What does the text imply about Shechem’s power?

- What are the differences between how the men involved see the episode? How do Yaakov, Chamor and the brothers see what happened?

- How could the brothers do what they did?

The traditional reading of this episode [Genesis 34, read it here] will be influenced by Rashi. Rashi will blame the entire episode on Dina, and of course, her mother Leah. Calling them both yatzanit, goer-out, he points out that were Dina not going out to see the girls of the land, like her mother who goes out to get a night with Ya’akov in exchange of the mandrakes (we saw this last week) nothing would have happened. [Read it here]

Many commentators disagree, but it is important for us to make sure we understand that there is this position in our tradition. The strongest voices against Rashi come from David Kimchi, Abarbanel and Luzzatto.

David Kimchi (Radak, Provence, 1160-1235) admits that were Dina to stay in, nothing would have happened and that that was Leah’s fault. However, he also points out that there is a midrash that looks with askance about Dina in the previous story, the encounter of Yaakov and Esav. In that midrash, Dina was hidden by Yaakov inside a chest, so that Esav would not see Dina, and not request to marry her. (Genesis Rabbah 76:9) The question revolves, too, on the fact that Shechem is not circumcised, whereas Esav was.

Abarbanel (Isaac ben Judah Abarbanel, Portugal, 1437-1508) says that the blame is actually all Yaakov’s. He was the one who decided to buy land there, and pitch the tents near the city. If he was so worried about his daughter, he should have pitched the tents farther away. Moreover, to buy the plot he obviously had to invite Shechem, who saw Dina. He goes on to actually defend Dina’s reputation, saying that Rashi is completely wrong and that Leah was a modest woman, who stayed in the tents – the one going out pasturing sheep is Rachel. And then he adds something else: Dina is the only young woman in that entire household. She has no sisters. And of course, he says, she went out with company – as Moses did when Moses goes to see his father-in-law.

Luzzatto (Shadal, Shmuel David Luzzatto, Italy, 1800-1865) defends Dina from the accusation of doing anything wrong: he says she just wanted to see the clothes and the women – and this is just what women do, there is nothing wrong. And he adds that, when he saw the Samaritan version of the Torah, it is not written “to see”, lir’ot, but “to instruct”, leharot, leaving us with a higher image of Dina than we would have.

A final voice for this moment in the discussion, much older than Rashi but apparently unknown to him, is a midrash collection called Pirkei deRabi Eliezer (Israel, 3rd century CE). On 38:1 it calls our attention to the verse that says that Shechem desired Dina the daughter of Yaakov – that Shechem had seen the tents pitched and wanted the wealth as well as the girl, so he send women to play music on pipes in the streets, and as soon as Dina came out drawn by the noise, he takes her. So depending on where you look, you will see different positions regarding Dina’s agency – and by comparison, the agency given to women in general.

Now, let’s talk about the case itself. There is a dispute on whether this is rape or seduction. Rape is an objective crime, seduction is much more complicated. And you understand the different reactions of the males in the story by separating these two ideas.

Those who see this as rape point out to “lay with her by force.” But this is a question of translation – the word “yeaneha” actually means “mistreated her” or “he humbled her” – and it is used in several other instances, but not in rape. This mistreatment of the body can be self-inflicted, imposed, or willing, and is used to describe fasting (Vayikra 23:32), slavery (Bereishit 15:13), and even adultery (Devarim 22:24).

The Tanach talks about rape in different moments – and in all those the expressions are chazakah – lit. force, or tefisa – lit. seizing physically (see Deuteronomy 22:25-28; II Samuel 13). Both are missing from this story. There is no expression by Dina of screaming or trying to ward off Shechem. The verb used is lakach, to take, an ambiguous verb that is used also in marriage (to take as a wife.) The Tanach also knows about seduction, and in the case of a woman not betrothed, they must get married (Exodus 22:15-16) or the father receives the bride-price, whatever the father decides. Jewish law later, due to rabbininc enactments, will make sure that in the case of marriage the woman has the final say in any instance.

But back to our case – compare Dina’s case to the case of rape of Tamar by Amnon. As soon as he is done, he casts Tamar into the streets (II Shemuel 13:15-19). The idea is that once the act of violence is completed, from the psychological standpoint, the usual case of rape results in disgust on the part of the rapist for his victim. And this is why in Deuteronomy the rapist is punished by having to marry and never to divorce his victim unless she desires it (Devarim 22:29). But look at Shechem – in the aftermath we read “his soul clung to Dina… and he loved the girl, and he spoke to the girl’s heart” (34:3). They are either inside the palace or they go into the palace later.

With those possibilities in mind, we can try to position each of the male characters. Each reaction is paired with a verse:

Yaakov (“for Dina his daughter had been defiled” [v. 5]);

The sons (“for an abomination had been committed in Yisrael” [v. 7]);

Chamor (“Shechem my son longs for your daughter” [v. 8]).

Yaakov sees his daughter as defiled because she had relations with an uncircumcised male. His baby, unaccustomed to the attentions of men she is not related to, has been taken advantage of by the local prince, a youth who may have slept with half the girls in his town already, for whom “I want, I have” is pretty much the law: this is not exactly democracy. Perhaps she even believes she is in love with him. Yaakov is upset but what can he say? He is learning all this through this visit of the king, Chamor, who actually wants the two young people to marry. Maybe Yaakov does not want to leave his daughter in the hands of this man, but he cannot force her to leave either. Uncharacteristically, Yaakov is quiet and reminds us much more of Yitzchak.

For Dina’s brothers, this is a clear-cut case of rape – statutory rape, perhaps, but the legal difference is not so important. “For an abomination had been committed in Yisrael, to sleep with a daughter of Yaakov – such cannot be done!” They are incensed. They feel dishonored and decide to act with guile, convincing the townspeople to circumcise themselves. Shimon and Levi, the zealots, alone murder every male, but all sons help in the plunder (v. 25-28).

Chamor sees this as a case of young love. Apparently, he is serious, seeing a full socioeconomic assimilation in his town’s future. Indeed, his townsmen see circumcision as a prerequisite for the assimilation of Yisrael amid the Chivi. They suspect nothing, since they see nothing wrong with the whole situation – and even if they did, who among them was going to go against the future king?

Dina, clearly, is not part of the conversation. She is not given the chance to say she wants – or not – to marry Shechem. Her only active part is going out. In all the rest of the story she is passive, and is only mentioned as an independent person at the end, on verse 26. She is seen as a figure, property, really, and the words to describe her will describe to whom she “belongs” – a girl to become a wife, a daughter, a sister. The story is much more a story about the positions of the men regarding Dina than of Dina herself. But that she might have been a willing participant is also underscored by what the brothers say at the end: is she to be treated like a prostitute? Prostitutes typically engage in sexual activity willingly, whatever your thoughts about prostitution might be.

Now, even though all brothers are together to take Dina back, only two are filled with blood lust. The brothers say twice that the only guilt here is “defiling” Dina. They do not even bring up the abduction – maybe because there was none. Maybe they all understand, through Chamor, that Dina went willingly. But that does not matter – it was the honor of the males that they go to punish the city. Yet Shimon and Levi go on to do an indiscriminate killing.

In terms of social conventions, if the seductor and the seduced were Israelites, they would be married. But this story comes to talk about the intermarriage with idolaters, circumcised or not. In this case, the polemic is very strong – and it has reverberations later in Deuteronomy and Ezra-Nehemiah. But neither of those two books have the violent reaction of Shimon and Levi. That is so beyond the pale that Yaakov objects strongly at the end of the story, and will not forget this when he dies, cursing them (Gen. 49:5-7):

“Simeon and Levi are a pair;

Their weapons are tools of lawlessness.

Let not my person be included in their council,

Let not my being be counted in their assembly.

For when angry they slay men,

And when pleased they maim oxen.

Cursed be their anger so fierce,

And their wrath so relentless.

I will divide them in Jacob,

Scatter them in Israel.”

Levi, we all know, gets no land – they are scattered in towns and are not landowners. Shimeon, as a tribe, eventually has land, but it is an enclave inside the tribe of Yehuda (See map here). Rashi, looking at this much later, will say that “all the very poor, such as scribes and elementary teachers, are all from the tribe of Shimeon.” Levi, without any land, has to serve in the temple and “go around collecting the tithes and gifts to the levites and kohanim” (Rashi on Genesis 49:7), a step up from begging, but not by much.

If the reaction of Yaakov in the beginning has to do with practicality, we see that it morphs to moral at the end of his life. Not only what Shimon and Levi did was morality wrong, but also it demonstrated even less consideration for Dina’s welfare than the laws in Exodus and Deuteronomy.

Dina will disappear from the Torah, but the daughter that she has with Shechem, according to the midrash, will be Asenat (Pirkei deRabi Eliezer 38:1-2). Asenat will marry Yosef. This last midrash is really looking to find a silver lining in all this, one of the most difficult stories of our patriarchs.

Shabbat Shalom.

The angel and the storyteller

Our portion is Vayishlach, and it is the last one where angels figure extensively through one of the patriarchs, Ya’akov (Jacob). With next portion, Vayeshev, the presence of angels will diminish – Yosef has no encounters with angels. But angels will continue to figure prominently throughout the Jewish tradition, even though that imagery is recreated by Christians, and many Jews do not talk about angels at all. This is a traditional story that comes from Poland, in which angels play an important part, and in which a Talmudic discussion about one specific angel, Layla, is the background [you can read it by clicking here].

Long ago, in a place not far from here, there was very pious rabbi, wise and knowledgeable in Kabbalah. He had a wife whom he loved dearly, and she loved him back. The couple was always at peace, and that happiness was only darkened by the fact that they had no children. Now, because of his knowledge of Kabbalah, one of the things he did for the people in the town was to write amulets for the women who had a hard time conceiving. As soon as the woman put the amulet around her neck, which had the name of the angel Layla, who is responsible for conception and pregnancy, she would become pregnant.

After many years, his wife finally asked him the question: ‘Dearest, if your amulets are so effective, why don’t you write an amulet for us?’

‘The people of the town need amulets to strengthen their faith in the Holy One, dearest. Our faith is strong, so we don’t need amulets. I am confident that God will send a child to us, we just need to be patient.’

That very night, both the wife and the husband had a vivid dream, with a beautiful woman, who called herself Laylah. She was the angel. And she told them: ‘The Holy One of Blessing has heard you. You will have a child within a year. The only request is that the child be named Shmuel (Samuel).” When they awoke, they were amazed to discover they had the same dream. And true, in a year she gave birth to a baby boy.

When he came out, after the midwife cleaned him, his skin shone and illuminated the bedroom. It was clear that this was a very special soul. But he was different than any other baby the midwife had ever delivered: ‘Look at his lips!’ she said ‘I have never seen a baby born without the separation on the top of the lips!’

As mother and child were resting, the husband came in and said: ‘This light that surrounds him is proof! Here is a very special soul, just like the angel Layla promised us!’

‘Do you know my friend Layla?’ a voice suddenly asked.

‘Who said this?’ asked the rabbi, amazed to hear a voice that was not his or his wife’s. ‘I did, I, you son’, the voice responded.

The rabbi’s wife sat on the bed and said: ‘But you are only an infant!’

‘Yes, mother’, the baby continued, ‘but the angel Layla gave me a great gift. She touches all other babies above the lips to make they forget everything they learn in their mother’s womb. But Layla let me retain all my memories. I still have work to do in this world.’

‘What do you mean?’ asked the rabbi.

‘Bring everyone of the town, everyone who wants to listen to a great story, and I will tell it.’

So the rabbi was seen like a madman, running around town, inviting everyone to their home, telling them that the newborn was speaking like a grown up man. And of course, even those who thought the rabbi had lost it on account of being a father, came to check things out. And suddenly, the small home of the rabbi was filled with people. The infant began speaking, to the amazement of all.

‘As you know, my name will be Shmu’el. As all other babies, I come to this place with the help and supervision of the angel Layla. She brought my body and soul together, and taught me from the Book of Mysteries, and she teaches every soul before they arrive to this plane of existence. But she flicks her fingers under the noses of the soon-to-be-born, so they will forget all they learned, and will discover the world anew, making new mistakes and discovering new happinesses. But Layla did not do that to me, because I have unfinished business.

In my previous life I was a storyteller named Shmu’el. I would travel from city to city weaving my tales and creating new stories, teaching Judaism through them. I became famous, as did my stories. And after many years of doing so, I felt it was time to retire, so I let people know I was going to tell my last story and that all were invited to listen. People came from all over, and from the very first word I felt this was going to be special. From the very first word, people were listening like a trance, nothing existed for them but my words. But I did not get to finish my story, my heart gave out in the middle of it.

The uproar on earth was only matched by the uproar on heaven. The angels too wanted to hear the end. As I arrived in Gan Eden, I was surrounded by angels wanting to know how the story ended. But I refused to tell them, because I thought it was unfair – people on earth were my main listeners, they were more deprived than the angels.

They insisted for years, and for years I refused. After 300 years, they finally gave up, and they requested that I be allowed to come back so the tale can be finished. That is why Layla permitted me to remember everything. So now I will begin telling the story again.’

And as Shmu’el began telling the story, a great wind filled the house, and people were amazed to feel and see angelic presences all around them. The tale was long and complex, and lasted many hours. But no one thought about leaving, they were in a trance, drinking the words of Shmu’el, just as they were when he told the tale the first time. Morning came, and still no one moved.

As the tale ended, Shmu’el felt a great relief, and all the angels began singing. The angel Layla stepped in, a beautiful woman, kissed Shmu’el on the head and told him this was the greatest tale ever told. She then gently flicked Shmu’el in the space between the nose and the lips. He closed his eyes, and went to sleep.

All the angels departed, including Layla. The baby awoke as people were leaving, and the only thing he could remember was how hungry he was. His mother fed him, and he was just like us – a newborn ready to make new mistakes and discover new happinesses.

Shabbat Shalom

Vayetze ~ Departures and growth

Vayetze is a fundamental portion for our collective historical arch in the Torah. It brings the birth of the carriers of the story onwards – the children of Yaakov, who will become the Children of Israel. Many of the stories we read in our portion have correlations with other sections in the Torah.

Vayetze is a fundamental portion for our collective historical arch in the Torah. It brings the birth of the carriers of the story onwards – the children of Yaakov, who will become the Children of Israel. Many of the stories we read in our portion have correlations with other sections in the Torah.

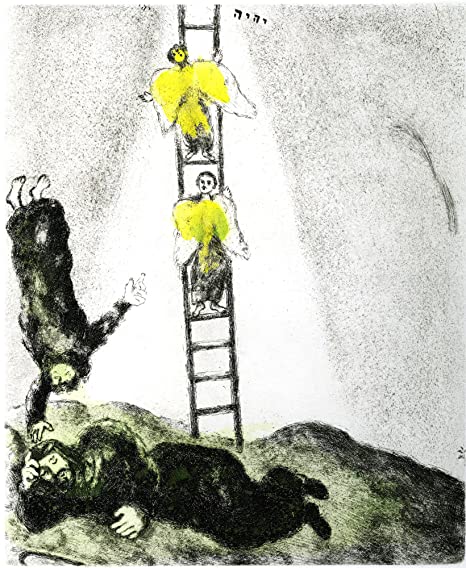

The portion opens with the famous dream of the stairs. This will be the final connection between Yaakov and Avraham – the blessing bestowed by God, marking Yaakov as chosen. Vayetze marks interesting changes and departures from the previous patterns: up to this moment, each patriarch had two sons, and one is chosen while the other is not. In Yaakov’s case, all children will be chosen – even though we know one will still be favorite. The sheer number of children will break with the pattern of two children before: Adam and Chava, Avraham, Sarah and Hagar, and Yitzchak and Rivkah. The competition for Divine favor, which marked all the previous notable families, also ends here. Yosef will have a leadership role, but not a special blessing.

In terms of collective arch, Yaakov and Avraham will be connected also through the foreshadowing of slavery in Egypt. Avraham has this both in the “sister-wife” narrative involving Pharaoh (Gen, 12:10-20) and in the Covenant between the Parts (Gen. 15:1-15). Yaakov will actually live the foreshadowing, and the signs are found in our reading.

The trickster will be tricked time and time again, and what was supposed to be “just a few days, until your brother cools down” (27:44) will become 20 years.

Our triennial picks up here, with yet another trick by Lavan.

~ What is the trick? How is it solved by Yaakov? How do you understand the solution proposed?

~ Can you find word connections between this moment and the slavery in Egypt?

~ What is the relationship between Rachel and Leah, and Lavan?

The trick that we read in our triennial is the change, again, of the wages of Yaakov by Lavan. This time, before God tells Yaakov it is time to go back, Yaakov himself wants to go back (30:25). But he remains, not due to a command from God, but because of a new transaction between him and Lavan. What are the words Lavan uses? “I learned by divination that I have been blessed by God because of you.”

And so Yaakov stays a few more years, his ego satisfied, apparently, by the words of Lavan, and by the promise of “doing something for my house” (30:31). This is eerily similar, in theme, with the sale of the birthright by Esav. With Esav, the moment of hunger took over from the larger picture, the birthright. At this moment, the moment of “making something of himself” takes over the value of going back to his family.

I don’t know about other immigrants, but Brazilian people that go back to Brazil for a visit usually spend an enormous amount of money on new clothes and gifts to everyone (the Brazilian idea of family is much more encompassing than the American) in part because they, like Yaakov at this moment, want to go back showing that they accomplished something in America.

But apparently it is all good, just as the birthright sale was, because there is no intervention by God. The intervention comes later on the portion, when God Godself talks to Yaakov and tells him to go back (31:3) – and now Yaakov can’t postpone it, for many reasons.

One of the reasons is that he, indeed, made something of himself – apparently, again, from nothing. The agreement he reaches with Lavan is that he will keep all the spotted, speckled and dark-colored animals. And Lavan will keep all the white ones. Lavan, true to his name, agrees. But true to his character, before Yaakov can select the animals, he himself takes away all the speckled, spotted and dark-colored – leaving Yaakov with only white ones to tend – meaning, Yaakov again gets nothing.

And then comes a scene that is the strangest for us: the shoots of poplar, almond and plane trees are peeled, creating markings – and all the sheep that mate looking at those shoots, give birth to speckled animals. The three types of trees have a function: poplar grows fast, plane is resistant to disease and has clusters of seedballs, finally, almond grows fast and gives almonds in clusters as well. The imagery of growing fast, healthy and plentifully should not be lost here. And if genetically it seems impossible, keep in mind that for very many generations there was a different concept regarding reproduction – what you see and think at the moment of conception is what happens. This was regarded as true with humans, all the more so, in this text, it should apply to sheep.

This theory is called “maternal impression” and it was alive and well until the 19th century. We know this because of the famous Elephant Man, about whom it was believed that his deformities came from his mother having been knocked over and frightened by a circus elephant. This idea is present also in several Rabbinic accounts.

In terms of maternity impression, the portion in its totality brings the mothers to fore. It is the competition between Leah and Rachel that brings an end to the competition between the children, by breaking the pattern of two boys per couple. They are also the ones giving the names to the children, with one exception – Levi. While Rachel is loved because of her beauty, Leah ends up being respected because of the sheer number of children she gives to Yaakov.

Yaakov remains attracted to Rachel – she is so similar to him in many aspects, besides being beautiful: a trickster herself, she steals the household idols (not in our triennial) and then dupes her father. In the intense desire to have children, she gets her sister to give the mandrakes to her, by selling Yaakov for one night – is this type of exchange not familiar?

Leah, on the other hand, is described only through her eyes. In Hebrew, rakot, translated variedly as weak, tender, moist. This should remind you of another set of eyes – Yitzchak’s. The other set of eyes mentioned in the Torah, which grow weak (27:1). And you probably heard the maxim “the eyes are the window to the soul.”

In that sense I think the sisters are symbolizing the two realms that are pulling Yaakov – the daily grind, the desire of “making something of himself”, of material growth and beauty and the impulse of this moment versus the higher thinking, the spiritual desire, the wanting to be part of Avraham’s blessing. It is looking at Yaakov through these lenses that we can understand his transactional reaction to the vision of the stairs: “If God does this and that… then God will be my God, and I will give 10% to God. (28:20-22)”

This is also how we can understand this entire portion, and why the rabbis cut the story the way they did – the portion opens and closes with Yaakov meeting God at the beginning and God’s angels at the end. But inside are all of Yaakov’s very human dealings: running away, relying on his physical strength, falling in love, dealing with Lavan, becoming rich and having many children without any divine intervention.

Yaakov, just like us, is pulled between two visions – the spiritual one, represented by Leah, and the physical one, represented by Rachel. And in the moment, the small daily tasks, God does not seem present for Yaakov – who still relies on incredible encounters that will remind him of his own need for growth. It is that presence, working in the background through none other than Lavan – who is initially told by divination of the presence of God (our reading, 30:27), and then through a dream (31:24); and he is the one to remind Yaakov of God’s protective presence.

The same dynamic will happen many generations later with the Exodus of Egypt, also foretold in our portion through the linguistic and thematic similarities: both Pharaoh and Lavan look at the Israelites and Yaakov differently, both outsmart them into working or slavery, both the Israelites and Yaakov increase and prosper, both depart at night with spoils, both are protected by God in their run. The Israelites will time and again openly doubt Moshe, and Yaakov still needs visions to keep him going. Both climaxes will happen near water – the struggling with the angel and the renaming of Yaakov, the finally believing in God with the Song at the Sea.

And that same dynamic is present in our own lives – how many times have you, just this past year, struggled to find God, or a higher purpose, or a transcendent moment in your daily life? All of us are still searching for a higher meaning, to make a difference, to connect with something that gives us purpose. And how much are we pulled between that desire and the desire of material growth, of success, of fame?

This is even present in how Thanksgiving happens in America – we give thanks and then proceed on Black Friday to buy everything we see we don’t have. The same pull is there.

And just as Yaakov we keep trying, and some times succeeding, to remind ourselves to follow our better selves, or higher calling, our true values, our spirituality. May this week that opens be such a week: of growth, of touching the intangible, the ineffable. Shabbat shalom

Toldot ~ Speaking freely in the second Jewish family

Toldot is the one reading that is dedicated to Yitzchak alone – and Yitzchak’s character and personality are not very developed since he is squeezed between two strong characters, Avraham and Yaakov. He also marries a strong woman, which is Rivkah.

Early in the reading we learn that both parents chose to prefer one of the twins: Yitzchak likes Esav and Rivkah likes Yaakov. We also know that Rivkah knows that the older will serve the younger. We also know that, coming hungry from a hunting trip, Esav sells his birthright for lentil stew.

And then our reading opens with Yitzchak making a peace pact with Avimelech, and becoming blind after that. Then the scene of the blessing happens, and I am purposefully being vague because I want you to think for yourself.

One of the most tragic images of the Torah is the sobbing of Esav when he realizes he will not receive a blessing. Even though the triennial reading ends on verse 27:27, I would like to invite you to read a few more verses, up to verse 38. So please find that in your chumashim, to have the full vision of the scene of the blessing. The scene begins on verse 1 of chapter 27.

Do you think Yitzchak knows which son is in front of him?

What do you think of Rivkah’s involvement in all this?

Yaakov will be seen as a trickster from now on. Does he deserve the title? How many times does he lie? Why does he lie?

Look closely to the communication between the members of this family. Does Rivkah tell Yitzchak that the older will serve the younger? Does Yitzchak tell Rivkah he is about to bless Esav? Do the boys tell their parents about the selling of the birthright?

==================

As we look at the story, we know a few things: Rivkah knows who the rightful heir is. The boys have made one of those exchanges that siblings do, and never tell their parents. What is not clear is what Yitzchak knows. There is a lot that is not clear about Yitzchak’s position in all this: is he a victim? A willing participant? Is he really going to die? We know he isn’t, he lives many many years after this.

One of the things that is clear, however, is his preference for Esav, who is favored by Yitzchak early on. Yitzchak appreciated that he was a hunter, in contrast to the homebody that was his brother Yaakov. Esav is more an “adult” than Jacob: he had married and may have already provided Yitzchak and Rivkah with grandchildren. He is also a good cook, besides being a good hunter: for all the lentil stew of Yaakov, it is Rivkah who prepares the meal, since she knows how Yitzchak likes it, and clearly Yaakov does not. But as favored as he can be, his choice of wives makes both Rivkah and Yitzchak unhappy.

Rivkah, overhearing the request for a wild animal, takes the driver seat. Yaakov does not seem to have a moral quandary – he worries only about what the consequences might be if he gets found out. He does depend on Rivkah for the preparation of the meal. I am not an expert, but I am going to guess that it is hard to make goat meat taste the same as wild game.

It is Rivkah that I am most impressed by in this scene. Not only does she solve the second problem quickly and easily, she demonstrates that she is willing to put everything on the line to do what she sees as God’s will. When Yaakov is worried that he will be cursed– a natural fear given the circumstances– Rivkah is willing to step up and say, “let the curse fall on me”. She has courage and conviction – even though we might be uncomfortable with what she is doing with them. If Yitzchak curses his son, Rivkah agrees to take the curse on herself. That suggests that her motivation is not selfish, but rather something that she does for the long-term good. Yaakov’s motivations are never so altruistic.

Let’s look at Yaakov. He lies three times at least, if you don’t count the dressing up as a lie. So he does seem to deserve the trickster title, and it is seen as ‘just deserts’ by some commentators the fact that he will be the one tricked over and over by Lavan. It is hard to like him.

Yitzchak seems to be fooled, but we are never so sure. With the verse “the hands are the hands of Esav, but the voice is the voice of Yaakov” one could see him as playing along. Rashi will tell us that Yaakov cannot but give himself away – he can’t speak the way his brother does to his father.

קֽוּם־נָ֣א שְׁבָ֗ה וְאָכְלָה֙ מִצֵּידִ֔י (27:19) Please get up and sit, and eat of my game.

How did you find it so quickly?

הִקְרָ֛ה ה אֱלֹהֶ֖יךָ לְפָנָֽי׃ (27:20) Ad-nai your God made it come to me.

To this, Rashi comments, bringing a midrash: Isaac said to himself, “It is not Esau’s way to mention the name of God so readily, and this one says, “Because Ad-nai your God caused it thus to happen to me!

It is Rashi who will, time and again, try to clean up Yaakov’s act, showing that Yaakov chose his language carefully so as not to lie (Click here). It is Rashi and many midrashim who show Yaakov as a simple bookworm, sitting in the tents, learning. I find this a little farfetched given their birth: Yaakov is already grasping the heel, and when he sees an opportunity, he buys the birthright. So he is trying, even though he is not as strong or mature as his older brother, to grasp the first place.

And maybe that is why Yitzchak plays along: he realizes how far Yaakov is willing to go to get this blessing.

The Netziv (Rabbi Naftali Tzvi Yehudah Berlin, 19th century) proposes a different vision for Yitzchak: he wants the brothers to get along, to share. He’d rather bless Esau with birkat haaretz (the blessing of the land) – physical plenitude and mastery over the physical world and bless Yaakov with birkat Avraham (the blessing of Avraham) which Yaakov actually receives when he goes to Lavan’s house. That was the blessing that Avraham received ensuring that his descendants would be God’s chosen nation (28:3-4, we did not read this in the triennial). Yitzchak had no reason to think that one of his sons would be rejected. He believed they would both lead this chosen nation as partners, with Esav mastering the physical world and Yaakov carrying on the spiritual legacy. (See Haamek Davar ad loc, click here for the text)

It’s Rivkah that knows this can’t be, because of her prior knowledge of “the older will serve the younger.” And Rivkah is also the sister of Lavan. She will send her preferred son to learn from Lavan, maybe to become the adult that Esav already is – there, away from the house. Maybe she realizes that Yaakov does not have the space to develop into the grand destiny of that prophecy.

Notice that Rivkah had already received Avraham’s blessing (from her own family) to have descendants by the “thousands and tens of thousands . . . to gain possession of the gates of their enemies” (Gen. 24:60). That is a repetition of the blessing given by God to Avraham at the end of the akeda. “Your descendants will gain possession of the gates of their enemies” (22:17). And as I said, will be the blessing given to Yaakov at the end of our reading.

Something that has always bothered me is that in the scroll, Rivkah is called a “na’ar” (a masculine form for an unmarried person at marriageable age) four times when she is introduced (see 24:16,28,55,57 – click here) and she is never called using the feminine form “na’ar’ah.” We read it as na’arah, “maiden”, and that is how we translate it. But that is not what is written. The use of the masculine for her, four times, implies that this is not a mistake but a decision of some sort. And maybe this is a way of signaling that that she gets the mission to carry the blessing, not her husband, in a very patriarchal society. It fits in her general sketch: she is beautiful, but strong – remember watering the camels? And once she puts something in her head, she will see through it (there are 10 camels, 40 gallons per camel, 8 pounds a gallon, you make the math.)

This is what I think is the detail we have to pay attention in this story, and this is definitely a lesson we can take home: the couple does not talk about their hopes for the kids. The kids don’t talk about their internal exchange with the parents. It really appears that Rivkah never told Yitzchak of the encounter with God, which is very odd for expectant parents. And this is what is important: the secrecy is what makes this story happen, and all its eventual heartache – what Rivkah says will be “but a few days” will become 21 years of separation.

Shabbat Shalom.