The portion begins with the plagues of locusts and darkness, and its bulk is the death of the firstborn and the going out of Egypt.

Bo is the parsha of the Exodus, in the sense that it is here when we read the last night of the Jews in Egypt. It is in Bo that three of the four children, with their questions, appear. “When your children ask: what is the meaning of this for you?”; “When your child asks: what is this?”, and “you shall say to your child”. These are known as the wicked, the simple and the one who does not know what to ask.

Notice that we celebrate Pesach today as one big holiday, but it is actually composed of two, both mentioned in our portion: Chag HaPesach and Chag Hamatzot – the festival of the Passover sacrifice, lasting one day, and the Festival of Matzot, that lasts 7 days.

Our portion makes clear that there are two different Pesachim (plural of Pesach): Pesach Mitzrayim and Pesach LeDorot, that is, the First Passover; and the celebration of Passover for all generations. For instance, we do not smear our doorposts with blood nowadays, but the did that in Egypt.

The image of the Jews painting our doorposts is a fairly famous one. Look at the text – this command is repeated twice. Why do we have to paint the mezuzot with blood? Where do you think this blood is – in the inside or the outside of the door? Who needs to see it, and why?

====

The first thing I want us to notice is the preparation for that moment: the text says – the lamb was to be selected on the tenth of the month, kept separated and guarded, and then slaughtered, roasted and eaten.

According to historians, rams were seen as a symbol of fertility in the Egyptian pantheon and were identified with various gods. Ram-headed sphinxes flank the entrance to the temple of Amun at Thebes. The bodies of some rams were mummified and equipped with gilded masks and even jewelry. So there is quite a statement being made here, which is, we, slaves, will take the symbol of the deity – a one-year old ram – slaughter, roast it, and eat it. The blood will mark our doors. Nachum Sarna affirms that there is a process of making the interior sacred, marking the difference between interior and exterior.

A collection of Midrashim, the Mekhilta deRabbi Yishmael, offers three possibilities:

“(Exodus 12:7) “And they shall place it on the two side posts and on the lintel”: on the inside. You say on the inside, but perhaps on the outside (is meant)? It is, therefore, written (Ibid. 13) “And I will see the blood” — blood which is seen by Me and not by others. These are the words of R. Yishmael. R. Nathan says: On the inside. You say on the inside, but perhaps on the outside? It is, therefore, written (Ibid.) “and the blood will be for you as a sign” — for you and not for others. R. Yitzchak says: On the outside — so that the Egyptians see (their gods being slaughtered), and their insides be “ripped apart!”

The midrashim usually have no problem with presenting different opinions without harmonizing them. Each of these three opinions hold different attitudes. God wants to see the sign – in part because, as the midrash explains next, once the destroyer is out and about there is no distinction between good and bad people. So the destroying force, which is clearly not very bright, needs a sign to do precisely what the term Pesach means – skipping. The third opinion holds that it is an outside sign, but God is not the audience. The audience are the Egyptians, who will see their gods being slaughtered. That is the symbolic act of leaving idolatry.

The second opinion that holds that the sign is for the inside, is the one that interests me more this year. The audience is the Jews themselves.

There is this interesting idea that four things were kept by Jews in Egypt, which was why they were redeemed, but God’s worship was not one of them. There are four things: Jews kept their names, their language, the idea of not speaking lashon hara, and the idea of not being promiscuous. (Vayikra Rabba 32:5 and other places). Which points to another idea, popularized in the 16th century, that we were almost not redeemed, we were steeped in 49 gates of ritual impurity. 50 is the maximum. Those four things – the names, the language, the value of faithfulness and not gossiping are the hook that made it possible for us to get out.

So marking the door has a lot with us choosing to continue the Jewish experience – with us actively choosing to be, not passively being chosen because we are descendants of Avraham, Yitzchak and Yaakov. That idea is not present in the Book of Exodus at all. The escape from Egypt has to do with a promise made to Avraham, and not so much with a choosing that God makes about our people. The idea of choseness comes later, after the giving of the Torah, and our accepting of it. And then the choseness is not unconditional, and does not point to an ineffable essence, but to acts and actions, mitzvot.

And if we think about it, how could God be choosing Jews in Egypt when we did not even know God that well? Remember, the plagues are not just for Pharaoh’s benefit – the plagues surely are an answer to Pharaoh’s question “who is God that I should let Israel go?” – but the plagues are even more a question of teaching the Israelites who God is. Next week, in Beshalach, we will read that once we have seen 10 plagues, once we were at the Sea seeing the Egyptian army drowned, “the Jews believe in God and Moshe”.

We know that a mixed multitude came with us, they saw the possibility of freedom and took it. But we also know that the desire to go back to Egypt will not leave the Jews for forty years. Poor Moshe has no idea yet, but soon he will know. And why we will want to go back? For the menu, the leeks, the cucumbers, the fish, the meat. And you could imagine that there were those who decided to stay behind, who didn’t want to go out. Who liked fish, cucumbers and leeks so much that they thought they were a fair price for freedom. Those did not mark their doors, sealing their fate forever, disappearing from our people –later also forgetting names, language and values.

So I believe that the blood on the door is actually for us, it is our moment to say “I’m in”. The Zohar affirms that at that fateful night in Egypt we are not simply smearing the blood on the frame and the doorposts – we are writing three yuds, one on each piece of the door, and that is the sign. In some old prayerbooks you can still find God’s name portrayed like this. In the Zohar’s imagination, the door is always there – every time you pray. Because as the distance grows between the miracles in Egypt and us we understand much more the nature of the miracle. It is a constant choosing to be Jewish, keep Jewish, act Jewishly. It is as much a miracle of God as it is a miracle of the people: keeping, against all odds, the flame alive.

May we continue to do so this week, keeping the flame, the continuity, the mitzvot, Hebrew.

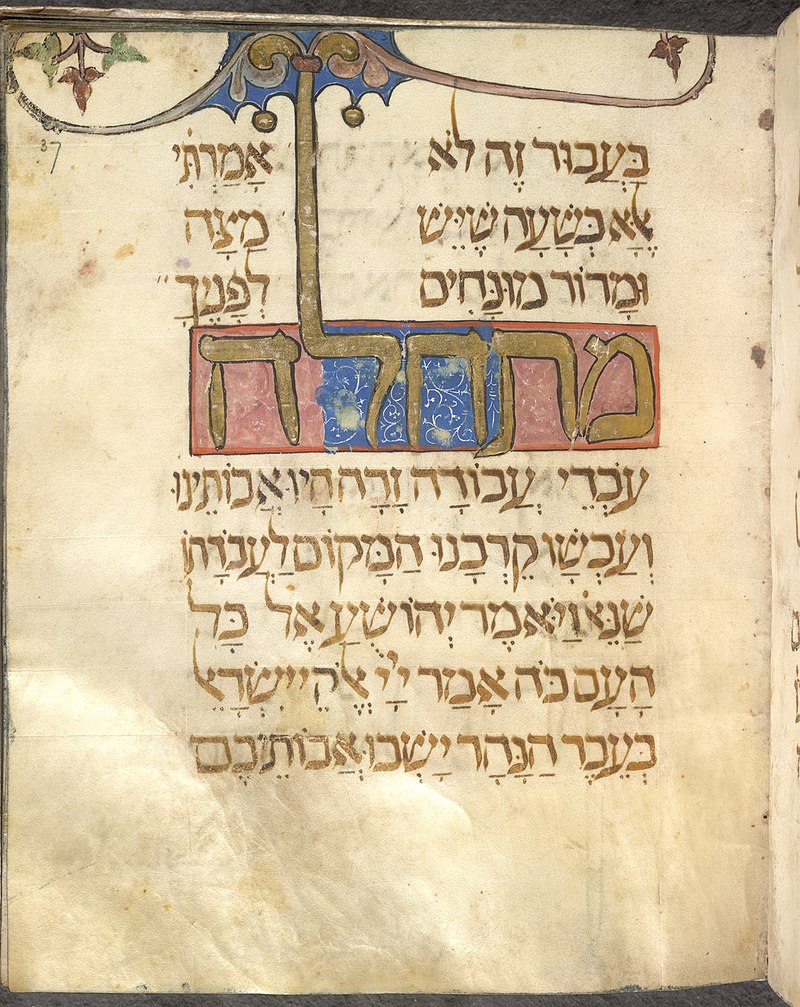

< page for the “Haggadah Hermana” or “the Sister Haggadah” manuscript (Spain, 13th century)