Vayetze is a fundamental portion for our collective historical arch in the Torah. It brings the birth of the carriers of the story onwards – the children of Yaakov, who will become the Children of Israel. Many of the stories we read in our portion have correlations with other sections in the Torah.

Vayetze is a fundamental portion for our collective historical arch in the Torah. It brings the birth of the carriers of the story onwards – the children of Yaakov, who will become the Children of Israel. Many of the stories we read in our portion have correlations with other sections in the Torah.

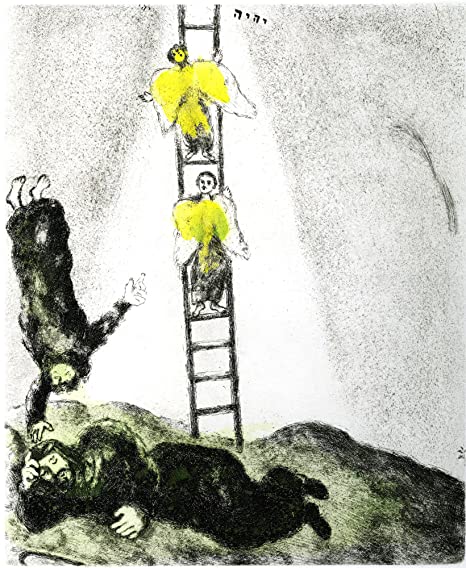

The portion opens with the famous dream of the stairs. This will be the final connection between Yaakov and Avraham – the blessing bestowed by God, marking Yaakov as chosen. Vayetze marks interesting changes and departures from the previous patterns: up to this moment, each patriarch had two sons, and one is chosen while the other is not. In Yaakov’s case, all children will be chosen – even though we know one will still be favorite. The sheer number of children will break with the pattern of two children before: Adam and Chava, Avraham, Sarah and Hagar, and Yitzchak and Rivkah. The competition for Divine favor, which marked all the previous notable families, also ends here. Yosef will have a leadership role, but not a special blessing.

In terms of collective arch, Yaakov and Avraham will be connected also through the foreshadowing of slavery in Egypt. Avraham has this both in the “sister-wife” narrative involving Pharaoh (Gen, 12:10-20) and in the Covenant between the Parts (Gen. 15:1-15). Yaakov will actually live the foreshadowing, and the signs are found in our reading.

The trickster will be tricked time and time again, and what was supposed to be “just a few days, until your brother cools down” (27:44) will become 20 years.

Our triennial picks up here, with yet another trick by Lavan.

~ What is the trick? How is it solved by Yaakov? How do you understand the solution proposed?

~ Can you find word connections between this moment and the slavery in Egypt?

~ What is the relationship between Rachel and Leah, and Lavan?

The trick that we read in our triennial is the change, again, of the wages of Yaakov by Lavan. This time, before God tells Yaakov it is time to go back, Yaakov himself wants to go back (30:25). But he remains, not due to a command from God, but because of a new transaction between him and Lavan. What are the words Lavan uses? “I learned by divination that I have been blessed by God because of you.”

And so Yaakov stays a few more years, his ego satisfied, apparently, by the words of Lavan, and by the promise of “doing something for my house” (30:31). This is eerily similar, in theme, with the sale of the birthright by Esav. With Esav, the moment of hunger took over from the larger picture, the birthright. At this moment, the moment of “making something of himself” takes over the value of going back to his family.

I don’t know about other immigrants, but Brazilian people that go back to Brazil for a visit usually spend an enormous amount of money on new clothes and gifts to everyone (the Brazilian idea of family is much more encompassing than the American) in part because they, like Yaakov at this moment, want to go back showing that they accomplished something in America.

But apparently it is all good, just as the birthright sale was, because there is no intervention by God. The intervention comes later on the portion, when God Godself talks to Yaakov and tells him to go back (31:3) – and now Yaakov can’t postpone it, for many reasons.

One of the reasons is that he, indeed, made something of himself – apparently, again, from nothing. The agreement he reaches with Lavan is that he will keep all the spotted, speckled and dark-colored animals. And Lavan will keep all the white ones. Lavan, true to his name, agrees. But true to his character, before Yaakov can select the animals, he himself takes away all the speckled, spotted and dark-colored – leaving Yaakov with only white ones to tend – meaning, Yaakov again gets nothing.

And then comes a scene that is the strangest for us: the shoots of poplar, almond and plane trees are peeled, creating markings – and all the sheep that mate looking at those shoots, give birth to speckled animals. The three types of trees have a function: poplar grows fast, plane is resistant to disease and has clusters of seedballs, finally, almond grows fast and gives almonds in clusters as well. The imagery of growing fast, healthy and plentifully should not be lost here. And if genetically it seems impossible, keep in mind that for very many generations there was a different concept regarding reproduction – what you see and think at the moment of conception is what happens. This was regarded as true with humans, all the more so, in this text, it should apply to sheep.

This theory is called “maternal impression” and it was alive and well until the 19th century. We know this because of the famous Elephant Man, about whom it was believed that his deformities came from his mother having been knocked over and frightened by a circus elephant. This idea is present also in several Rabbinic accounts.

In terms of maternity impression, the portion in its totality brings the mothers to fore. It is the competition between Leah and Rachel that brings an end to the competition between the children, by breaking the pattern of two boys per couple. They are also the ones giving the names to the children, with one exception – Levi. While Rachel is loved because of her beauty, Leah ends up being respected because of the sheer number of children she gives to Yaakov.

Yaakov remains attracted to Rachel – she is so similar to him in many aspects, besides being beautiful: a trickster herself, she steals the household idols (not in our triennial) and then dupes her father. In the intense desire to have children, she gets her sister to give the mandrakes to her, by selling Yaakov for one night – is this type of exchange not familiar?

Leah, on the other hand, is described only through her eyes. In Hebrew, rakot, translated variedly as weak, tender, moist. This should remind you of another set of eyes – Yitzchak’s. The other set of eyes mentioned in the Torah, which grow weak (27:1). And you probably heard the maxim “the eyes are the window to the soul.”

In that sense I think the sisters are symbolizing the two realms that are pulling Yaakov – the daily grind, the desire of “making something of himself”, of material growth and beauty and the impulse of this moment versus the higher thinking, the spiritual desire, the wanting to be part of Avraham’s blessing. It is looking at Yaakov through these lenses that we can understand his transactional reaction to the vision of the stairs: “If God does this and that… then God will be my God, and I will give 10% to God. (28:20-22)”

This is also how we can understand this entire portion, and why the rabbis cut the story the way they did – the portion opens and closes with Yaakov meeting God at the beginning and God’s angels at the end. But inside are all of Yaakov’s very human dealings: running away, relying on his physical strength, falling in love, dealing with Lavan, becoming rich and having many children without any divine intervention.

Yaakov, just like us, is pulled between two visions – the spiritual one, represented by Leah, and the physical one, represented by Rachel. And in the moment, the small daily tasks, God does not seem present for Yaakov – who still relies on incredible encounters that will remind him of his own need for growth. It is that presence, working in the background through none other than Lavan – who is initially told by divination of the presence of God (our reading, 30:27), and then through a dream (31:24); and he is the one to remind Yaakov of God’s protective presence.

The same dynamic will happen many generations later with the Exodus of Egypt, also foretold in our portion through the linguistic and thematic similarities: both Pharaoh and Lavan look at the Israelites and Yaakov differently, both outsmart them into working or slavery, both the Israelites and Yaakov increase and prosper, both depart at night with spoils, both are protected by God in their run. The Israelites will time and again openly doubt Moshe, and Yaakov still needs visions to keep him going. Both climaxes will happen near water – the struggling with the angel and the renaming of Yaakov, the finally believing in God with the Song at the Sea.

And that same dynamic is present in our own lives – how many times have you, just this past year, struggled to find God, or a higher purpose, or a transcendent moment in your daily life? All of us are still searching for a higher meaning, to make a difference, to connect with something that gives us purpose. And how much are we pulled between that desire and the desire of material growth, of success, of fame?

This is even present in how Thanksgiving happens in America – we give thanks and then proceed on Black Friday to buy everything we see we don’t have. The same pull is there.

And just as Yaakov we keep trying, and some times succeeding, to remind ourselves to follow our better selves, or higher calling, our true values, our spirituality. May this week that opens be such a week: of growth, of touching the intangible, the ineffable. Shabbat shalom