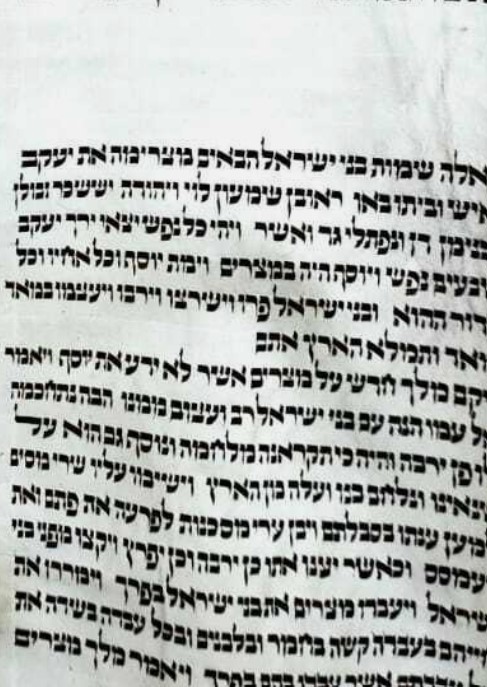

Shemot

Summary: The name of our portion is Shemot, which means “names”, and it is the beginning of the book of Shemot, or Exodus, in English. In terms of the arch of the story, we begin around 400 years after Yosef is arrives in Egypt, not only with the enslavement of the Jews but with the birth and rescuing of Moshe. The narrative will focus on Moshe and his development, to the age of 80, when he encounters the Holy One at the burning bush, and goes to Pharaoh to demand the release of the slaves. The portion ends with things getting worse before getting better, and Pharaoh forcing the slaves to collect straw to make bricks, while demanding the same amount of bricks.

==

KS – Names and Identity – Moshe

Our portion opens with the names of the sons of yaakov, but the text is already pointing out that there are people not named: we have the sentence saying “70 people came down to Egypt” while the names given are only 12.

Even Pharaoh is not named, and not even called Pharaoh at the beginning, but called “king”. The anonymity extends to all the courtiers of Pharaoh and all the maids of the daughter of Pharaoh, and of course to the slaves. People who will be the movers and shakers of the story – the mother, the father, the sister of the unnamed child who will eventually be named Moshe, as well as his savior, the daughter of Pharaoh, are all unnamed.

IN that sea of unnamed people, only two names will appear, and they are Shifra and Pu’ah, the midwives that dare to defy Pharaoh – the etxt appears to be raising women as leaders, and we will see that through the book of Exodus. But I want to call our attention to the question of the lack of names.

Even the name Moshe, Moses, is not a name in the Egyptian language – mss // child of / son of / Ramses, Tutmses as examples. The text gives a Hebrew etymology for his name, and many people point out the oddity to have Pharaoh’s daughter naming a child and giving him a Hebrew etymology. The lesson that applies to the character of Moses is that he is straddling two identities: Hebrew and Egyptian.

The identity of Moshe will be quite complicated: he goes out and sees his brethren, defends one by killing an Egyptian taskmaster, so he has some of the identity of a Hebrew. The next day, however, he sees two of his brethren fighting – and is rejected, being sent back to the identity of an Egyptian – just to have that taken away from him as well, with Pharaoh wanting to mete out capital punishment to him for killing the Egyptian taskmaster. He runs away – and the daughters of Yitro will say to their father that an Egyptian saved them. And once he runs away, to Midian, he becomes a Midianite – marrying Tzipporah, being quite content with his sheep and his children. At age 80, however, we know things will again change at the burning bush. When God meets Moses at the burning bush, the question of identity is implied in that encounter since God introduces Godself as “God of your ancestors” – which ancestors?

It bears noting that in the story of the Exodus, Moshe is the only Jew who knows what it means to be a free person, but he does not know what it means to be a Jew, and all those who know what it means to be Jew do not know what it means to be free.

In the text, we see Moshe skirting God’s call five different times. The first one is very telling: Who am I to go to Pharaoh? The question could stop in: But who am I?

The five times are also an indication of all the tensions within Moshe: the question of identity, lack of relationship with God, lack of relationship with the Jewish people as a whole (they will not trust me), lack of ability to speak, and just please, please find someone else.

It is not so different with us. We, just as Moshe, carry many different identities. American and Jewish are just two of the most glaring ones, but we have plenty smaller identities. Moshe also has an identity of being disonnected to God and the people, and an identity of disability. And God will not so gently push Moshe beyond those self-doubts and those fractured identities to an identity of someone who can do this. It is not so much that Moshe choses his Hebrew identity, but that he is able to understand himself as able to hold on to all those identities and not be pidgeonholed by any one of them. It is only when he moves to accept that yes, this is who he is, that he can move forward in the service of God. And so it is with us – once we can synthetize our many identities, then we too can move forward.

Shabbat shalom.

==

Shabbat morning

Our triennial focuses solely on the scene at the burning bush. How many times does God need to convince Moshe? Why do you think that Moshe is so unwilling to do what God is asking?

In your opinion, is Moshe different than others, and so that is why God is chosing him? Or is Moshe just a guy passing near a burning bush, and he happens to be in the right place at the right time?