Summary

These are the last parshiot of the book of Leviticus, of Vayikra. Next Shabbat we will be embarking in a different book, Bamidbar, or Numbers.

Behar actually means “On the mountain”, and this is Mount Sinai. Rashi will be quick to explain that what it means is that the Israelites did not really move for all that time we have been reading, and just as the Aseret HaDibrot, the 10 sayings, were given on Mount Sinai, so too all the rules we have been reading were given on Mount Sinai. The rules we read are the first set of rules concerning the Jubilee year, the Yovel. Among those rules are the mitzvah to help the impoverished among us.

Bechukotai means “in my rules”, and the idea is “if you observe My rules” all will be well. The a set of admonitions follows, a rebuke section, and the book closes anticlimatically with the valuation system applied to exchanges of gifts to the Tabernacle.

==

As we read, find the most famous quote of our portion. What it is, and where is it inscribed?

==

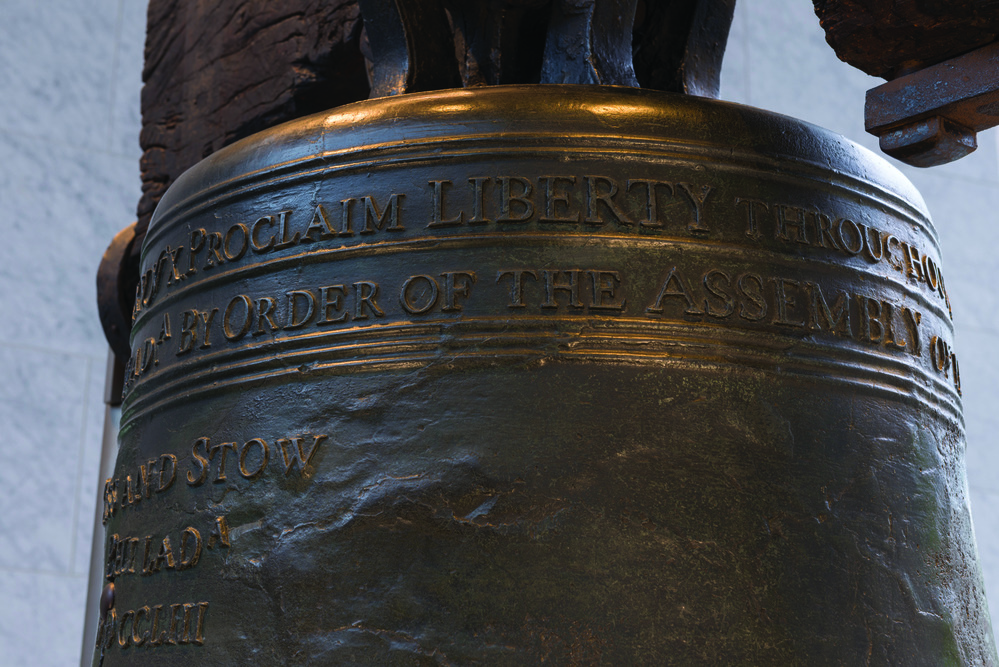

The most famous is 25:10 – “Ukratem dror ba’aretz, l’chol yoshveha.” “Proclaim liberty throughout the land, unto all the inhabitants in it.”

In our current political atmosphere, the words “liberty” and “freedom” have been used a lot. Now Isaiah Berlin, a philosopher of the 20th century has pointed out, in his essay “Two Concepts of Liberty,” that he sees two ideas of freedom, negative freedom and positive freedom.

Positive freedom means that there is no control whatsoever over my actions: I am the sole master of my actions. No external cause can affect me, and my decisions are based on my own ideas and purposes. Despite the name, positive freedom is not necessarily good.

Imagine someone who would decide to exercise positive freedom all the time, with no concern for other’s well-being. One example could be that such a person would never stop at a red light, given that this would mean that she will be two minutes late – and in the instance of receiving a ticket would fight for her right to cross the red light. Or that he will speak his mind, regardless of other people’s feelings; or even curse and belittle them, given that he has the need to express his frustrations. We would not think that this person is good, or nice, or right.

This idea, that freedom should entail no limit whatsoever, might seem idyllic to some: there are no limits to what you can do. There are no consequences. Or better yet – my freedom to do my will or my desire should be unimpeded by the rest of you puny humans.

Isaiah Berlin talks about the other concept of freedom, which he calls Negative Freedom. Despite the name, negative freedom is not necessarily bad. Negative freedom means that someone else, or something else has a control over my actions, whether the amount of control is big or small.

Imagine someone who would stop at the red light, given any amount of reasons, the greatest of which could be his concern for the other drivers’ safety. Or, he is careful with how he says things, so as to get his point across with a minimal amount of hurt caused on the other; or curb his anger at his co-worker’s inefficacy given that he holds the dignity of all people to apply in the same measure to the inept co-worker. We would not think that this person is bad, or nasty, or wrong.

Of course those two types of freedom can be at odds with each other, and can complement each other – it depends what you fight and whom you fight. And this applies, I think, to personal, communal and even national spheres.

When we look at the Liberty Bell, what liberty exactly do we think about?

That same question can be asked of the greatest American symbol, the Statue of Liberty. It was given by the French, I’m told, with the original title “Liberty Enlightening the World”. AND it was such a complicated gift that philanthropists had to scramble to procure funds to purchase a pedestal for the statue.

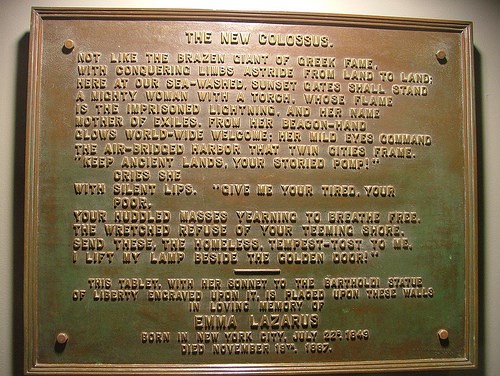

It was Emma Lazarus that redefined that gift into what became “Lady Liberty”. In her poem, called “The New Colossus”, she redefines what it means to enlighten the world:

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

In this poem, Emma Lazarus redefines liberty – the idea that freedom is where one can come and go, and live their life without oppression. This is very close to what the Talud will define as dror, freedom: Rabbi Yehudah says dror [refers to] “a person who can medayyer, who can live wherever they want, and do their business in the whole country.” (Talmud, Rosh Hashanah 9b) . Dror, says Rabbi Yehudah, is the ability of coming and going, doing business and making a living.

Now, making a living, in Jewish terms, means abiding by many rules – honesty and truth, in advertising and weights; not defrauding with words or deeds. It means accepting the idea that there are limits to your actions.

This same idea is brought by the rabbis when they discuss the description of the first set of the Aseret HaDibrot. There, the words were engraved on the Tablets, as Exodus 32:16 makes clear. The Hebrew is charut al haluchot, engraved on the tablets, yet the rabbis propose to read the text also as “cherut – al haluchot”. Freedom – on the tablets. There is no freedom unless you follow the Torah – meaning, freedom is great, but the Jewish idea of freedom is what Isaiah Berlin called Negative freedom. Freedom with limits to behavior.

The question that is on the forefront of our times is who has the power – who should have the power – to propose limits, and which limits should be proposed, and why.

Proponents of an idea of limitless freedom affirm that the only person to do that is the individual, as an island, deciding on his or her behavior, as they see fit, with no regard whatsoever to the idea of society. For them, liberty and freedom mean liberty from any sort of regulations and any attempt by the government to curtail those so-called freedoms is an attack on the idea of liberty.

Proponents of an idea of limited, rule-based freedom, affirm that the greater good determines what can be done, and accomplished. The question then becomes where do we receive the limits, the rules, from. What should be the source?

There are those who believe that religion should dictate that. Which religion? Theirs, of course. Which is the only truth, in fact. And that should scare us all, regardless of whom is proposing such. In part, because this has not worked well in the past, particularly for Jews, but in truth for all minority religions.

There are those who believe that the collective should dictate that, in a process of understanding basic texts that are foundational to countries – we usually call those texts constitutions. They propose a de-coupling of religion from power – and creating a space where all have some sort of say, majority and minorities, and no one is coerced to observe their religion, or any religion.

Those who know me, know where I fall in these possibilities. In part, it is because I believe in the concept of obedience to God has to be decoupled from oppression. As Rabbi Aaron Samuel Tamares wrote: “compulsory piety is an abomination.” Making people behave in the way you believe God wants them to behave is being just a different sort of Pharaoh, forcing people to act without their hearts being in it. That kind of obedience, coming from a place of fear, is not what religion means – which is connection to the presence of God.

I believe that we, all humans, have the capacity to connect to God, and the desire to do so, without being forced.

Shabbat shalom